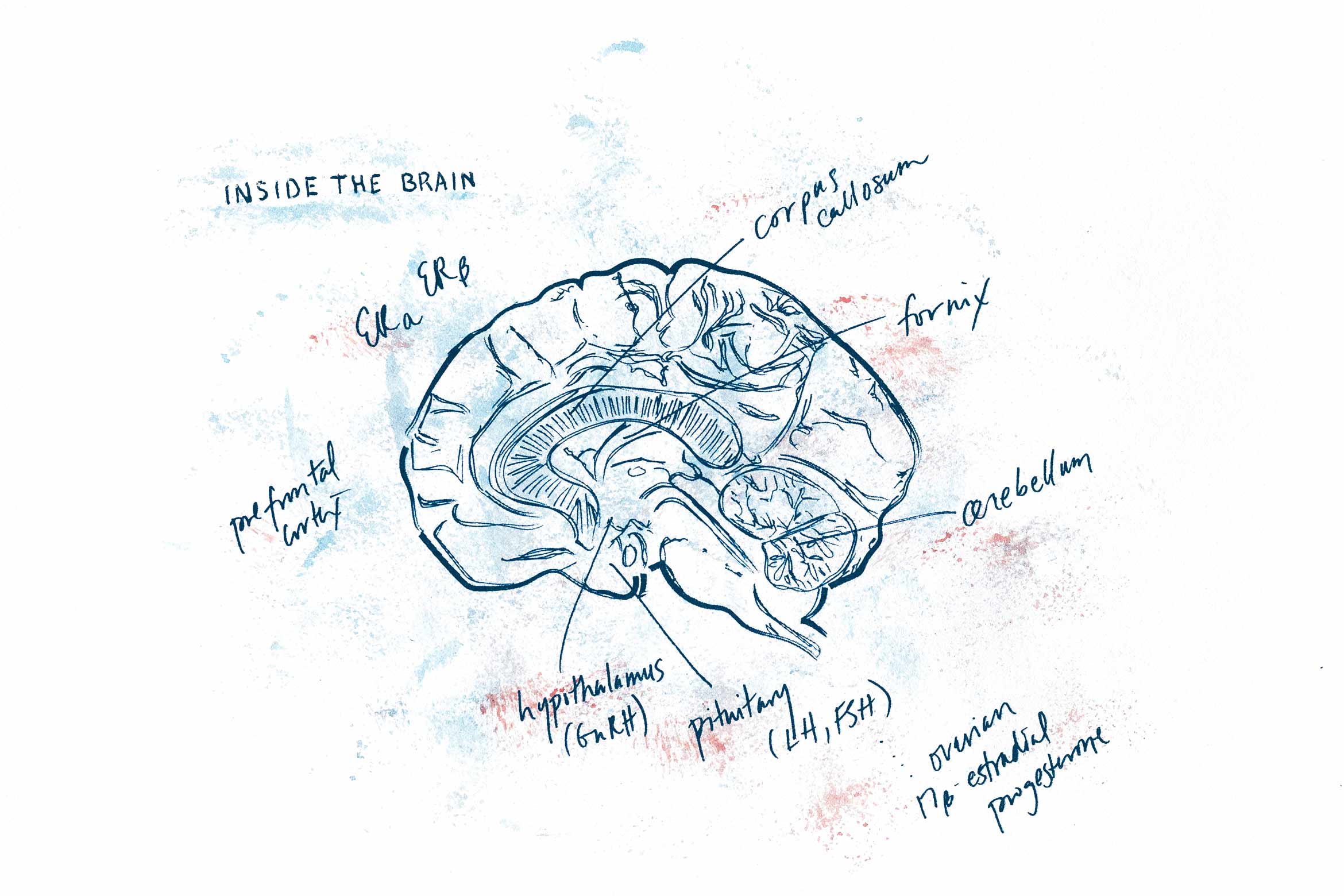

Much of Emily Jacobs’ research focuses on how sex hormones — estrogen, progesterone, testosterone — affect the brain. Where are they acting? On what circuits? And over what time span?

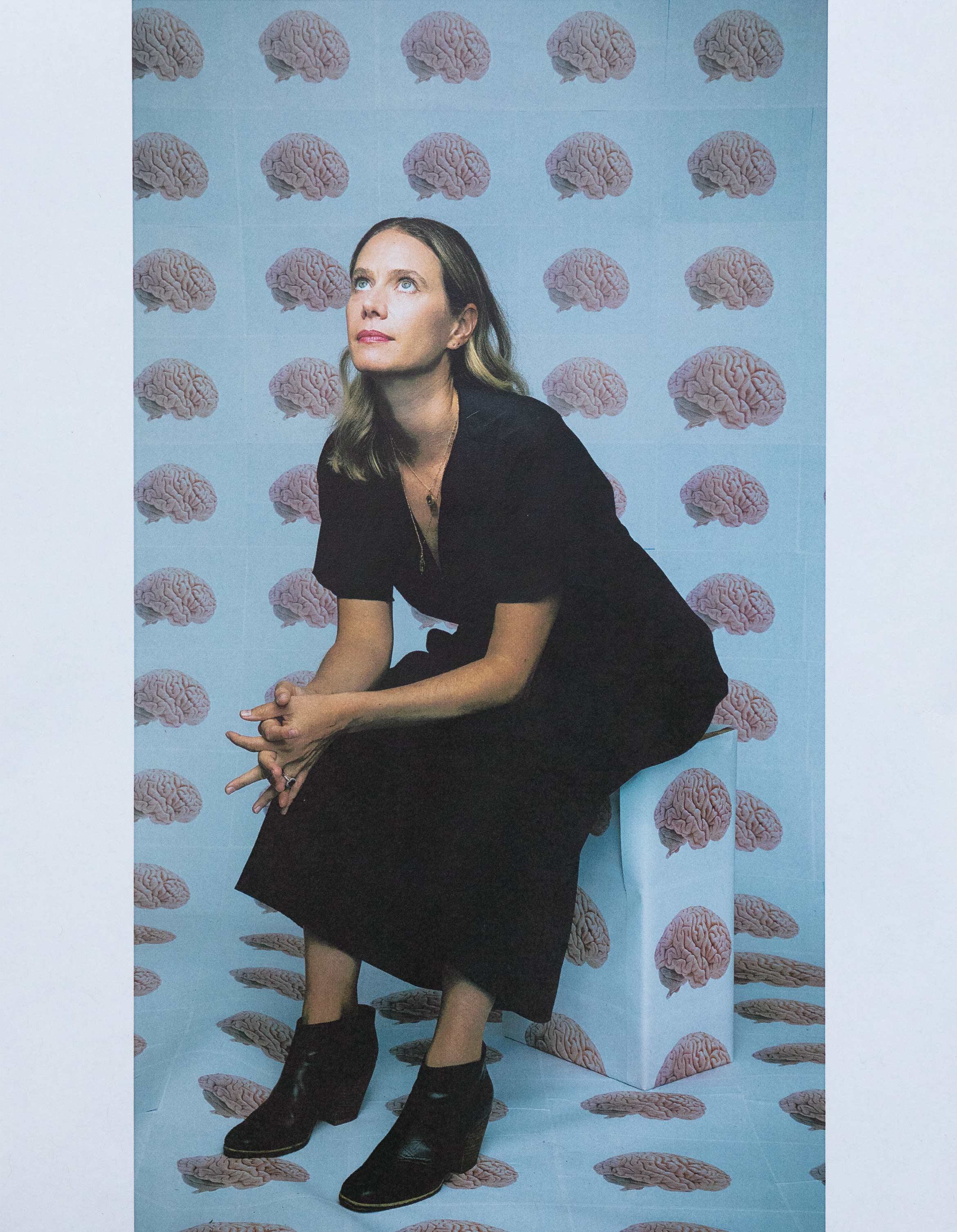

She studies these changes in both men and women, but Jacobs, a neuroscientist and a professor of psychological and brain sciences, is keenly aware that the female brain has, historically, been overlooked.

“Most of what we know about health and disease is centered on the male body,” Jacobs says. “Science and medicine have been fearful of women’s bodies for millennia. This dates back to Hippocrates, who suggested that a woman’s ‘wandering womb’ was to blame for any ailment she was suffering from. You can see traces of these myths today.”

These myths persist not out of willful ignorance or malice, Jacobs posits, but due to a lack of representation. “Neuroscientists know little of how menopause, pregnancy, the menstrual cycle and hormone-based medications influence the brain,” she says, “despite a growing awareness that gonadal hormones are critical neuromodulators of learning and memory.”

Could it be, she asks, that male scientists don’t think about the female body and brain because it is not central to their everyday lives? Jacobs has sought to correct this imbalance, pursuing studies that focus specifically on the brain during menopause, the menstrual cycle and pregnancy.

Therein lie the twin themes of her life: the power of scientific inquiry and the power of the female perspective. In all that she does, Jacobs puts women — their lived experiences, their health, their biology — at the forefront.

“For me and my lab,” she says, “shining a floodlight on women’s brain health motivates everything that we do.”

Charging Ahead

Named one of 10 scientists to watch by Science News in 2022, Jacobs, with her lab at UC Santa Barbara, is now leading a multicampus initiative to study female brain health, in partnership with UC Berkeley and UC Irvine. The project, the Women’s Brain Health Initiative, will pool data across several UC brain imaging centers to answer a large range of questions about how reproductive factors (such as the use of hormonal birth control or an irregular menstrual cycle) might shape the brain.

Jacobs says It all stemmed from a conversation with a postdoctoral scholar, Jacobs says, who approached her in hopes of studying the impact of hormonal birth control on the brain. After realizing that no large, systematic study had been conducted on the topic, Jacobs, acutely aware of the biases women face in the biomedical sciences, was irked — and inspired.

“Our hands were forced,” she says, “so we set out to create a large-scale brain initiative that was unabashedly, unapologetically for women’s health.”

After a successful pilot program, and with funding from the Noyce Trust and UC Partnerships in Computational Transformation, the Women’s Brain Health Initiative is poised to roll out across UC campuses. Female participants who come in for brain scans will be given detailed health history questionnaires, further boosting the strength of the imaging data already being collected. Jacobs and her team will then use that data to answer any number of unique questions about how hormonal factors affect the female brain.

“I have always been drawn to the tools of science,” says Jacobs, reflecting on what drives her to keep searching for solutions, “but the motivation to answer these questions comes, I suppose, from being raised in a feminist family, and realizing early on that I could use the tools of science to drive discoveries for women who have historically lacked that support.”

“I don’t think any other university in the world could do this the way that the University of California can,” Jacobs adds of the Women’s Brain Health Initiative. “UC brain imaging centers generate data from 10,000 participants annually. By harnessing that power and integrating neuroscience discoveries across campuses, we can usher in a new era of women’s brain health research.”