Written by Keith Hamm

Photos by Matt Perko

Written by Keith Hamm

Photos by Matt Perko

EARLIER THIS YEAR, onstage in front of a large audience of middle and high school students and their parents and grandparents, scholar Robin Nabi asked by a show of hands how many had a smartphone. “Silly question, right?” she commented as raised hands filled the gymnasium at Laguna Blanca School in Santa Barbara. She quickly followed up with another question she knew the answer to: “How many of you have been told that phone is bad for you, unhealthy, harmful?” Same show of hands.

Since the widespread arrival of smartphones to classrooms starting around 2012, conflicts between teachers and students have boiled over. These pocket computers and their social media apps are distracting and isolating and provide online playgrounds for bullies. At home, as well, parents have noticed that as screentime ramps up, their kids grow more withdrawn, anxious and depressed. Family tension can be compounded by the shame a parent may feel for failing to protect their child from real or perceived harms, even as parents themselves struggle with addictive doomscrolling and bingeing podcasts and TV shows.

During her recent TEDx Talk at Laguna Blanca, Nabi, a professor of communication at UC Santa Barbara, noted it’s gotten so bad and ubiquitous over the years that the 2024 Oxford Word of the Year was “brain rot,” defined as “the supposed deterioration of a person’s mental or intellectual state, especially viewed as the result of overconsumption of material (now particularly online content) considered to be trivial or unchallenging.”

But what if it’s not as bad as we think? That’s a fair question, says Nabi, an expert on the impacts of media on emotional health, decisionmaking, coping and overall well-being. In her TEDx talk, “Using Smartphones in Smart Ways,” Nabi invited her audience to take the proverbial deep breath and step back a moment to consider that American author Henry David Thoreau coined the term brain rot in 1854. Ever since, Nabi continued, brain rot has been linked to a long series of media forms — from comic book crime capers and the beguiling glow of television to video games, rap and heavy metal music and, of course, social media.

“Is there reason for concern?” Nabi asks. “Of course there is. But is there reason for panic? No.”

Professor Robin Nabi

Too much screen time — particularly related to social media use in kids, teens and young adults — is a major concern in modern society. Cellphones are ubiquitous. Social media is enticing. And the impulse-control and decision-making capacities in young brains are not yet fully developed. “Social media is the modern moral panic,” says Kylie Woodman, a graduate student in UC Santa Barbara’s Department of Communication and the Media Neuroscience Lab. “It’s everywhere. We see children, adolescents — even adults — glued to it. Yes, it can be a way to connect to others, but it also has an addictive aspect about it.” However, she adds, it’s important to remember, “This is not the first time we’ve seen something like this.”

Reading fever: In the 1700s across England and Europe, the widespread popularity of reading novels was causing young people to hole up, shirk responsibility and act out immorally. Reading fever, as it was called, was also blamed for a spate of suicides among fans of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s “The Sorrows of Young Werther,” first published in 1774. As the epistolary novel’s popularity grew, a sub-affliction — dubbed Werther fever — presented mostly among young men, who dressed as the protagonist and, pistol in hand, killed themselves in the throes of unrequited love. The book was banned in Denmark and Italy; for other fictional offenders, a sin tax was floated as a general countermeasure.

Radio: In the 1930s, a new household technology took hold of young people. In the U.S., parents became exasperated with their kids’ obsession with listening to the radio and blamed it for interfering with other interests, including reading, sports, playing music and participating in family conversations. Responding to content deemed overstimulating or inappropriate — such as the glorification of criminals in fictionalized dramas — parent activism prompted the National Association of Broadcasters to establish guardrails for children’s programming.

Television: Starting in the 1950s, televisions became standard in American homes. Not all shows were considered family friendly, however, and in 1969, the U.S. Surgeon General launched a three-year study of TV violence. The report’s summaries were mixed; while TV violence was found to promote aggressive behavior in some kids, it also put forth other considerations, including personality type, parental influence and local levels of violence. “Television is only one of the many factors which in time may precede aggressive behavior,” the report stated. “It is exceedingly difficult to disentangle from other elements of an individual’s life history.”

Video games: Video game popularity has been on an upward trajectory since the late 1970s. Research dating back to the early 1980s suggested that video game addiction was problematic among students. In 2018, the World Health Organization recognized gaming disorder as a mental health condition that intrudes on an addicted gamer’s sleep, work, education and ability to foster and maintain relationships in real life, while also impacting memory, attention span and stress management.

Social media: Social media addiction hasn’t been officially recognized, Woodman says, “but it’s pretty clear — at least within the literature — that it seems to be transposable to the extent that all the criteria for gaming disorder also apply to a social media or smartphone addiction.” “For teens and college students," she adds, "when you see those grades drop, that’s a big signal that their media use is actually becoming detrimental.”

Kylie Woodman, a graduate student in the department of communication, researches media effects at the intersection of communication, psychology and neuroscience.

Fundamentally, a smartphone is a handy tool to perform or facilitate certain tasks, not unlike a simple stick. As a tool, for example, a stick can be used to reach ripe fruit among the high branches of an apple tree. The same stick, however, can also be used as a spear. For parents, it’s easy to jump to the conclusion that children are always poking each other’s eyes out online.

Even small doses of social media can quickly reveal that these virtual gathering places are often more akin to a vicious battle in the Roman Colosseum than a cordial debate in the public square. “But when you really look at kids’ motivations and gratifications, oftentimes being on their phones is linked to something positive,” Nabi says. They’re learning new languages, recipes and Minecraft strategy. They’re learning how to ollie and to play chess and guitar. They’re listening to music and connecting with other kids with similar interests.

“Sometimes they’re using their phones for learning and social connection,” Nabi points out. “These are needs we all have as human beings.” In no way does she downplay connections between social media use and anxiety, depression, low selfesteem and disordered eating, among other maladies. “But if we focus only on the harms, we can miss the benefits,” she says. Recently, for example, preliminary studies by Nabi and her colleagues found no harm to well-being among adult users scrolling on their phones for five minutes; at the same time, other users who engaged with inspirational content experienced benefits similar to those who meditated for five minutes.

“This could be an example of how we can start thinking about the ways we can use media to uplift, to support, to enhance, so that we can make choices that can benefit us physically, psychologically and socially.” Just as mindless eating can be unhealthy, Nabi told the TEDx audience, “when we’re on our phones, we have to think about the content we’re consuming and how it makes us feel. You are in control of that tool in your hand.”

Like many families, Nabi and her husband started having conversations about smartphones and social media when their daughter was in sixth grade. They took a modified “Wait Until 8th” approach, a “no smartphone until eighth grade” parent pledge officially launched in 2017 by a Texas-based nonprofit. “We slowly on-ramped with a phone that was less expensive and didn’t have the temptations that come with smart technologies connected to the internet,” Nabi remembers.

“Our choices were based on who she is, as well as our priorities as her parents.” The next step — a smartphone — arrived when their daughter finished eighth grade. She had proved she could take care of her phone, not lose it, and not be distracted by it during school work or family time. The whole process has been a family conversation. That’s not to say they’ve never had a cross word over screens and phones.

“When you’re talking about tablet time for a 4-year-old, they’re not in a space to negotiate, but in junior high and certainly in high school, they have opinions,” Nabi says. “They know what they like and don’t like and what they think is fair. Including them in those conversations is really important so that they have some agency and a voice. Not having an authoritarian style around the phone issue means you’ll likely get more buy-in from your kid.”

With some negotiations and agreements, they set some house rules: no phone in the bedroom or at the dinner table. She keeps it on mute at school and while she’s doing homework. After a long day at school, she takes some downtime to decompress by watching videos and catching up with friends. Every family has its own dynamic, Nabi adds, “and we realize how very lucky we are that our daughter is not especially attached to her phone.”

“Every so often,” Nabi says, “we check in with her” about what she’s watching and how she’s feeling about the phone and all the things that come with it. “She’s aware that it can be addictive and that there’s a lot of information and imagery that’s inappropriate.”

Kids remember stranger danger from kindergarten, she adds, and for the most part, they’ve been taught to take the same precautions online. Nabi credits the schools for teaching digital literacy and online safety, and nonprofits such as Common Sense Media for publishing free, up-to-date, helpful resources for parents and educators. “Many families struggle with issues around screens generally and phones specifically,” Nabi says. “It’s important that we recognize that adolescents have the same needs and temptations as adults when it comes to their phones, and we as parents serve as role models for them on how to integrate these devices into our lives.”

“The key is keeping the lines of communication open about what our kids are doing online,” she says, “and perhaps we can even find opportunities to share those experiences and have more points of connection with them rather than strife.”

At UCSB, scholars like Nabi have long studied the complex relationships between media, technology and adolescent well-being. So when Jonathan Haidt’s “The Anxious Generation” burst onto the scene, framing smartphones and social media as the root cause of a mental health crisis among youth, it sparked immediate interest — and some debate — among experts in the field.

Since its debut in April 2024, “The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness” has skyrocketed to the top of bestseller lists and sold more than a million copies. A social psychologist and professor at New York University, Haidt has been touring extensively, giving talks to sellout crowds and sitting down with media giants, from “Good Morning America” to Oprah to Joe Rogan and Trevor Noah.

The book’s general theme is that we overprotect our kids in the real world as we underprotect them online. Too many of our kids have indoor, screen-based lives, Haidt says, often replete with bullying, fear of missing out, beauty shaming and disturbingly explicit content — and it has a negative impact on mental health and academic performance. Haidt’s book and speaking tours have stirred a grassroots movement of parents and educators as more and more school districts — even entire states and countries — have banned phones from schools entirely, not just during class time.

Author Jonathan Haidt on the UCSB Arts & Lectures stage discussing his best-selling book, “The Anxious Generation.”

Photo by David Bazemore

His argument to get phones out of schools isn’t controversial. Most educators and parents can get behind that. However, there’s been some frustration among researchers about how Haidt makes his case that smartphones and social media are rewiring kids’ brains for the worse.

“The high-level reviews of the published literature suggest that there is a small but significant relationship between social media use and anxiety and depression among adolescents,” Nabi says. “That same research also has found a positive correlation between social media use and social well-being. In other words, the relationships are smaller and more nuanced than Haidt suggests, and sometimes may even be positive.”

“The research is messy about whether or not social media is truly bad or good for you,” adds Woodman. “It’s not necessarily that a person gets on social media and starts becoming depressed. Some individuals already have a psychopathology of depression that’s leading them to develop a compulsive relationship with social media.”

Haidt and the movement his book has sparked promote four “achievable goals” they believe could create meaningful change: no smartphones before age 14; no social media before 16; phone-free schools; and more offline activities for kids. “We can fix this in three years,” Haidt says, “and it’s actually happening.”

For Nabi, the conversation Haidt has reignited is ultimately a meaningful one, even if the realities are more complex than his framing suggests. “As a researcher, it’s frustrating to see a scholar lean into a moral panic while dismissing evidence that doesn’t agree with their particular conclusion as it distracts attention away from addressing the larger factors influencing adolescent mental health,” Nabi says, “But to the extent that Haidt’s book has elevated the conversation around the challenges of phones in schools and protecting children from harmful online content, perhaps there is value there.”

Teachers have always battled fragmented attention spans and academic disinterest among students. The smartphone’s widespread classroom debut around 2012 has only made matters tougher. Over the years since, collaborations between parents, teacher groups and school board members have sparked policy efforts up the political food chain, from regionally elected leadership to state and federal educational and health agencies.

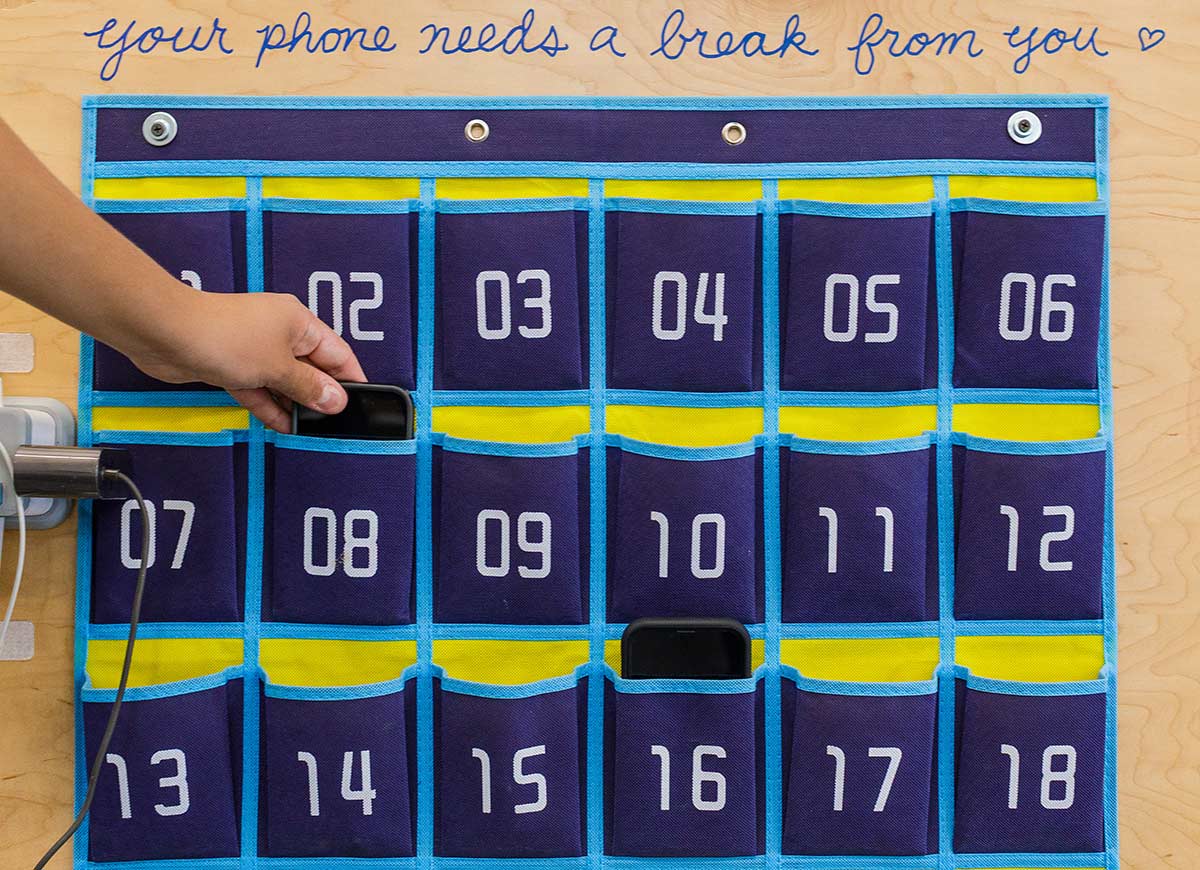

Locally: Santa Barbara County Education Office Superintendent Susan Salcido notes that policies regarding smartphone use are an overall priority but differ among districts. For example, in 2023, Santa Barbara Unified School District, which oversees roughly 12,000 students across 18 schools, enacted its “Off & Away” policy, requiring high school classroom “cell hotels,” out-of-reach dropoffs for devices.

Statewide: In an August 2024 letter to California public schools, Governor Gavin Newsom called on “every school district to restrict smartphone use in classrooms.” He followed up by signing the Phone-Free Schools Act (AB 3216), requiring that schools develop and adopt policies to limit or prohibit student use of phones at school.

Nationally: In December 2024, the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Educational Technology released “Planning Together: A Playbook for Student Personal Device Policies” to help guide policy on student use of personal devices. This April, the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services indicated it was working with states on "bell-to-bell legislation" to restrict the use of smartphones at school.