Professor John Martinis slept through the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences’ announcement of his Nobel Prize in Physics, and the subsequent deluge of phone calls to his Santa Barbara home in the wee hours on Oct 7, 2025.

“My wife was very kind to me and didn’t wake me up for a couple of hours because she knows that I need my sleep,” Martinis says. Eventually, though, the spate of calls did awaken him. That, and the reporter who showed up to their house at 6 a.m.

Similarly, his colleague, friend and fellow Nobel physics prize recipient Professor Michel Devoret noticed a flood of messages on his phone and computer throughout the morning and “thought it was a joke,” he would later say in an interview.

“I forgot October was Nobel Prize month,” he says. It wasn’t until he called his daughter in Paris that he ascertained that yes, he had actually won the prize.

Fortunately, by the time the pair realized they won — along with their erstwhile adviser, Professor John Clarke at UC Berkeley — they had had enough sleep to take on the whirlwind of interviews, calls and congratulations from family, friends, colleagues and former students.

Devoret and Martinis have brought the number of UC Santa Barbara faculty Nobel winners to eight since 1998; alumna Carol Greider, now a professor of biology at UC Santa Cruz, also received the 2009 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for work she accomplished at UC Berkeley.

“What a profound thrill, and a moment of exceptional pride for our campus, to congratulate our UC Santa Barbara professors John Martinis and Michel Devoret on winning this year’s Nobel Prize in Physics, alongside UC Berkeley’s John Clarke,” says UCSB Chancellor Dennis Assanis. Their wins, along with that of Cal’s Omar M. Yaghi, for chemistry, and UC San Diego alum Frederick J. Ramsdell, for physiology or medicine, bring the total number of Nobel laureates affiliated with the University of California to 49 — the most of any institution in history.

“These awards are not only great honors,” remarks UC President James Milliken, “they are tangible evidence of the work happening across the University of California every day to expand knowledge, test the boundaries of science and conduct research that improves our lives. I’m proud to see their work recognized.”

Devoret, Martinis and Clarke together were cited “for the discovery of macroscopic quantum mechanical tunnelling and energy quantisation in an electric circuit,” and lauded by the Swedish Royal Academy of Sciences for revealing “quantum physics in action.”

Little did the trio know their series of fundamental physics experiments 40 years ago would not only usher in an era of quantum science and engineering development, but also be recognized with the world’s most prestigious science prize.The application of their work to quantum processing and quantum information is undeniable, opening the door to breakthroughs in other realms such as cryptography and quantum computing.

How it started

It’s a long way from 1984 and 1985, when Devoret and Martinis were a postdoctoral researcher and a graduate student, respectively, in Clarke’s lab, seeking to answer a fundamental physics question: Do macroscopic variables obey quantum theory?

“Traditionally, and I still hear it often, quantum mechanics is the physics of small things, like atoms,” Martinis explains. “Normally, we think of how atoms work and how molecules bind together to form molecules.” The prevailing thought had been that quantum mechanical effects disappear at scales larger than atomic, in favor of classical physics.

However, theoretical research performed a few years earlier by Anthony Leggett explored the consequences of quantum mechanics being applied to collective variables inside a device spanning a very large number of atoms. This type of engineerable system could serve as a testbed for quantum mechanics.

“The idea that Tony Leggett had to test quantum mechanics was met with extremely strong criticism and skepticism,” Devoret recalls. “It was not the kind of thing you should be doing.”

But it was too enticing of a question for the trio to pass up. Armed with a burning curiosity, they turned to the Josephson effect. A phenomenon predicted in 1962 by theorist Brian Josephson, this effect occurs in a setup of two superconductors separated by a thin layer of insulating material, when electrons tunnel through the barrier from one superconducting layer to the other. The so-called Josephson junction would become a crucial part of their work.

At this frontier of new physics is where the gears began to turn. Devoret, Martinis and Clarke all fondly remember this time as an era of intense creativity, camaraderie and synergy among their diverse personalities and areas of expertise. And it led to groundbreaking problem solving as they devised a platform upon which to see if quantum effects — in this case, the collective quantum behavior of the current through the junction — could be observed via their cryogenic Josephson junction.

“It was marvelous,” says Devoret, who used his experience with cryogenics to design and build the dilution refrigerator that achieved the ultra-low temperatures required. Martinis would later credit his work with Devoret on the refrigerator with making him “fearless” to build the powerful and highly sensitive equipment needed to enable quantum mechanical effects in his later work.

Observing quantum tunneling on the macroscale had been attempted in a few experiments already, but Clarke, ever the adviser, challenged the junior researchers to find a way to make this experiment new, different and better.

“There had been some experiments, but they weren’t very complete and convincing,” Martinis recalls. “We figured out that we could measure the parameters entering in the theory more accurately than what had been done before.”

Their experiment afforded them the ability to finely control and tune their platform and precisely measure the phenomena that occurred when they passed a current through it. Importantly, while previous experiments involved only a few particles, the ones conducted by Clarke, Devoret and Martinis involved billions of electrons, bound together in pairs — “Cooper pairs” — that form when they are in a superconducting state.

The result? Evidence that the state of the circuit switched from being superconducting to dissipative, causing a voltage spike that appears across the junction. Additionally, the future laureates in their experiment were able to demonstrate the quantized energy states that define quantum mechanics.

“We had an oscilloscope and there was a trace on it that indicated when the junction switched (between voltage and superconducting states),” Martinis says. “I vividly remember at one point seeing this trace and seeing three dots on that trace.”

Classically, he explains, the graphical representation of voltage that the oscilloscope provides typically represents the change in voltage as a “smosh of a line.” However, the appearance of three dots indicates that the system absorbs or emits only certain specific amounts — “quanta” — of energy, true to prediction.

“When you see three little dots there, then you’re really seeing the quantum mechanics.”

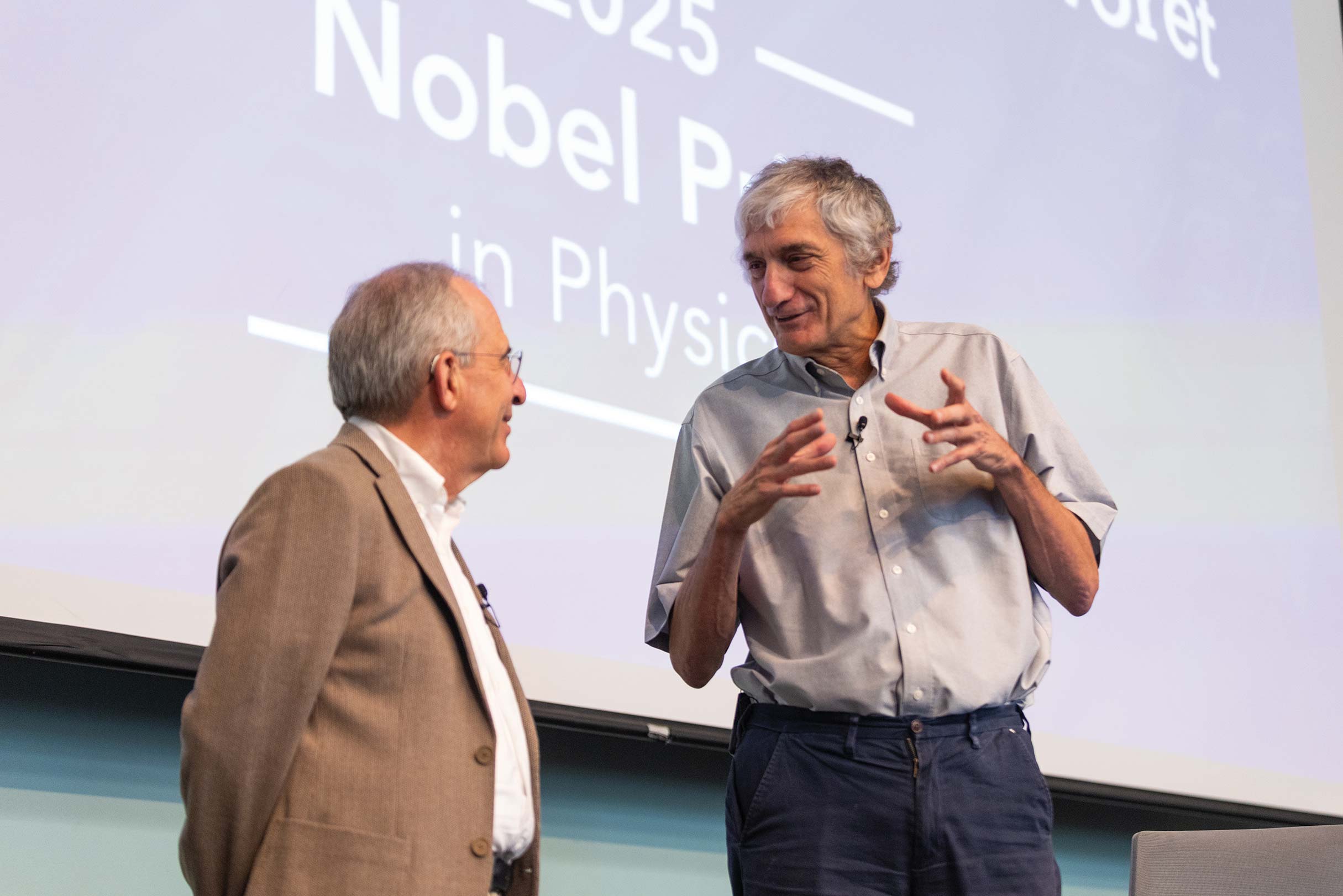

Michel Devoret and John Martinis talk on stage during the Physics Department colloquium.

Michel Devoret and John Martinis talk on stage during the Physics Department colloquium.