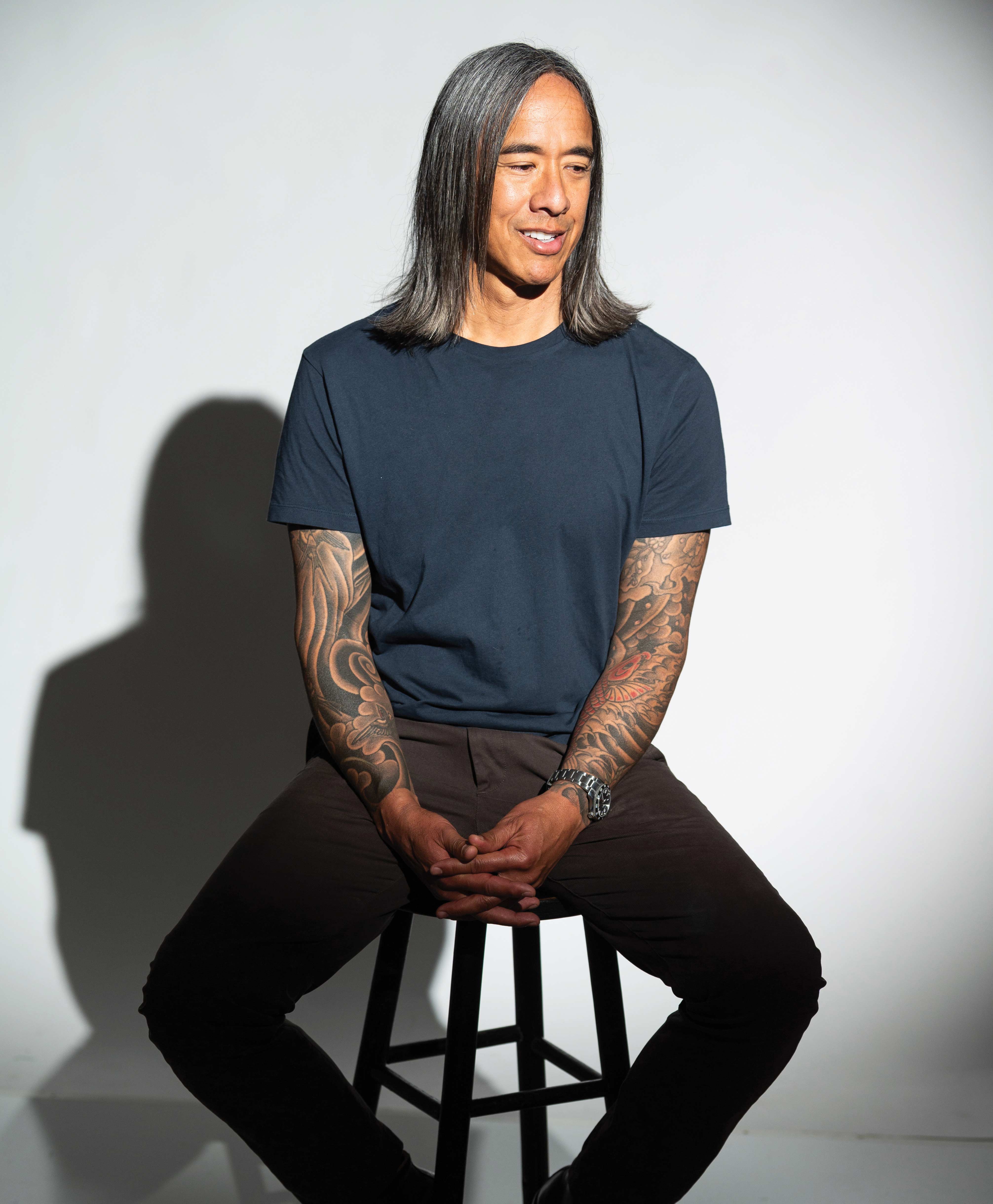

When artist and UC Santa Barbara professor Kip Fulbeck first heard the word “hapa” in the early 1970s, it came from a cousin. “I was the only mixed kid in my extended family,” he recalls. “My mother had immigrated from Taiwan with five children, all full-blooded Chinese. I was the outlier. To be told that I was ‘hapa’ — at the time, in Monterey Park, in what’s now called the First Suburban Chinatown — was both clarifying and complicated. My parents’ marriage itself would have been illegal in many parts of the U.S. just years before. Thinking of that now is bizarre by today’s standards, and rightfully so.” The Hawaiian word “hapa” — a transliteration of “half” — originated in the phrase “hapa haole,” or “half foreigner.” It was used by Native Hawaiians to describe children of Islanders and settlers. Over time, the word migrated to the mainland, becoming a marker of identity and pride for Asian and Pacific Islander Americans of mixed heritage. For Fulbeck, it became the foundation of his life’s work.

A landmark project

In 2001, Fulbeck began photographing people who identified as hapa, pairing their portraits with handwritten responses to a single question: What are you? The results became the groundbreaking exhibition (Japanese American National Museum, 2006) and book “Part Asian, 100% Hapa” (Chronicle Books, 2006). The portraits were stark and unadorned — no jewelry, clothing or props — to strip away assumptions and leave space for self-definition. “Participants pick their own photograph, handwrite their own statement, and — in the purest form — define themselves,” Fulbeck explains. The answers ranged from matter-of-fact (“A very littel [sic] boy that has no friends”) to profound reflections on heritage, alienation or belonging. The project resonated far beyond what Fulbeck expected. “For the original shoots, people just showed up,” he says. “In places like San Francisco or New York, there would already be a line outside before I’d set up. People wanted to be seen, to not be shoved into someone else’s box.”

Revisiting identity

Nearly 25 years later, Fulbeck has returned to the project with “hapa.me,” now showing at San Diego’s Museum of Us and the Museum of Chinese in America, New York. The exhibition pairs the original portraits with new ones of the same participants, alongside updated identity statements. “I wasn’t prepared for the overwhelming response,” Fulbeck says. “One person told me, ‘I’ve been waiting 15 years to be part of this.’ That’s when I realized how deeply the work mattered.” Reconnecting with participants was a challenge. “People had changed emails, moved or even passed away,” he says. “But every single person I found wanted to rejoin. That meant a lot.” The exhibition also invites new participants and museum visitors to contribute their own photos and handwritten statements, extending the dialogue.

Curating change

For Kate Clyde, senior director of exhibits at the Museum of Us, the project’s resonance is clear. “The response has been so overwhelmingly positive that our staff started calling Kip’s work ‘the people’s choice award,’” she says. “Visitors instantly connect with it. They see themselves — or their families — reflected in ways they rarely encounter in museums.” The museum has long engaged in community-driven conversations around race. Clyde notes that the project creates much-needed space for discussions of multiracial identity, particularly within Asian and Pacific Islander communities. “So much of the American narrative has been framed in Black-and-White terms,” she says. “But people told us they wanted more room for mixed-race stories. Kip’s work provides that.” Curator Francesca Du Brock, who recently hosted Fulbeck for a residency at the Anchorage Museum in Alaska, sees his approach as both bold and disarming. “He’s very down-to-earth and not afraid to talk about difficult topics,” she says. “That confidence makes others comfortable opening up.” In Anchorage, Fulbeck has photographed some 90 people, including Native Alaskans, Filipinos, Pacific Islanders and multiracial residents from across the state, as he prepares for an entirely new Alaska-driven version of “The Hapa Project” that will premiere at the Anchorage Museum in 2026. “The diversity here surprised him,” Du Brock says. “We have more than 100 languages spoken in Anchorage schools, and Kip felt it was important to include Native perspectives and broaden the project’s scope.”