When the U.S. Mint in 2022 released its Anna May Wong quarter, the fifth coin in the American Women Quarters Program, female Asian American representation got a boost. The following year, it had a pop culture moment when Mattel released the Anna May Wong Barbie, wearing a red dragon dress, in its Inspiring Women series. But who is Anna May Wong and what made her an icon?

Born in a Chinese laundry in turn-of-the-century Los Angeles, Wong rose to become Old Hollywood’s most famous Chinese American actor. Her performances captivated global audiences, but Wong faced serious challenges in an industry plagued by racism and sexism.

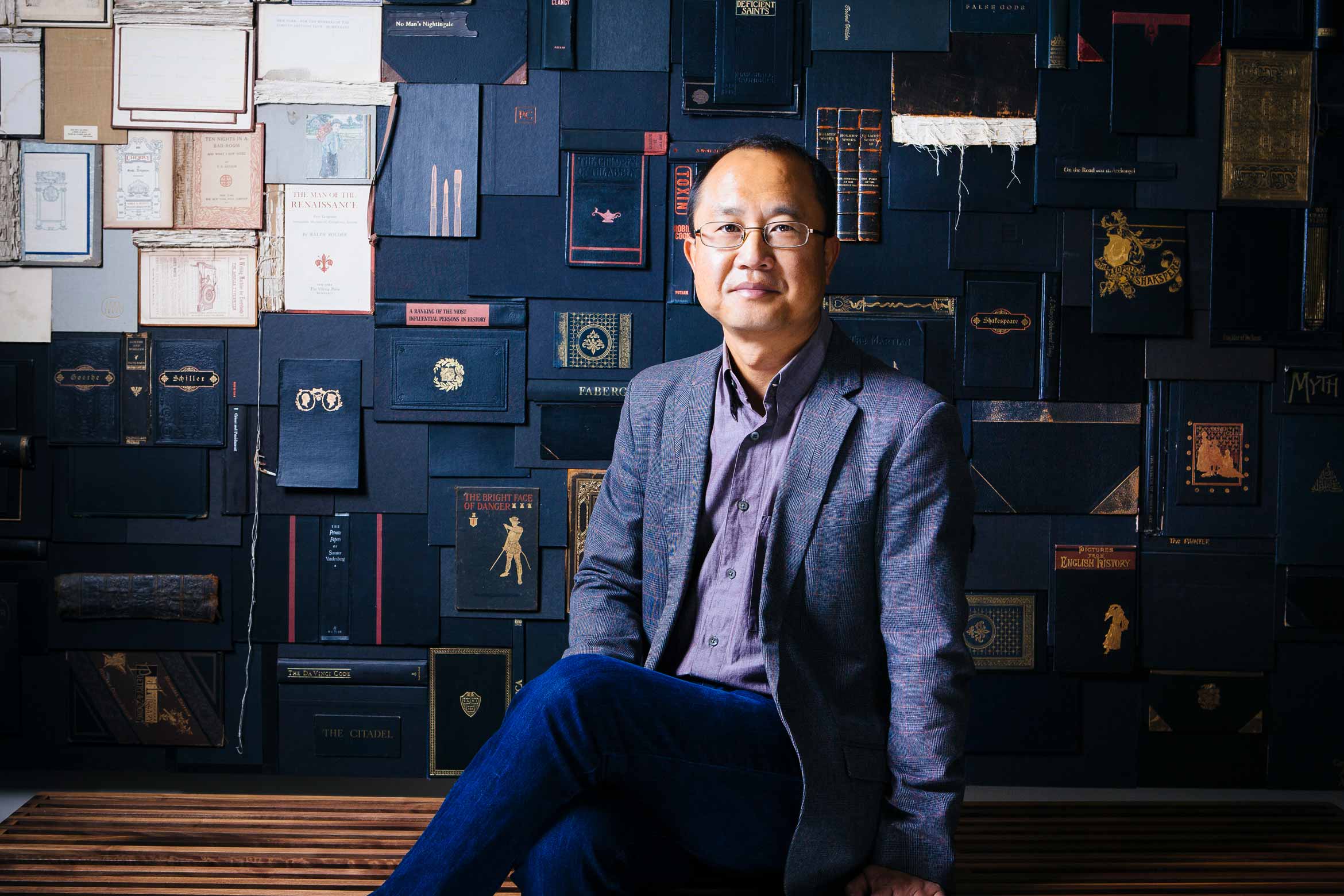

“America falls in love with Anna May Wong, but that romance is taboo and there are real costs that come from Anna May wanting to have and hold onto this love,” says Yunte Huang, whose biography on Wong draws from hundreds of her letters and other records. His portrait offers new insight into her rare talent and ambition as well as the historical milieu in which she lived.

“After all, she lived at a time when a Chinese actor would be deemed ‘too Chinese’ to play such a role — a cultural absurdity plaguing both Hollywood and Main Street USA,” Huang writes.

Her signature bangs, almond eyes and “willowy figure wrapped in a silky qipao (cheongsam),” as Huang writes, are mainstays of her iconic image. In 1938, she was immortalized on the cover of Look magazine with the headline, “The World’s Most Beautiful Chinese Girl.”

But Wong’s story is not just about glamour and fame. Huang, a poet, Guggenheim Fellow and a distinguished professor of English at UC Santa Barbara, traces her journey from Weimar Berlin to decadent, pre-war Shanghai, and captures American film in its infancy. Along the way, Wong encounters other remarkable people, including the philosopher Walter Benjamin and the actor Marlene Dietrich.

“Daughter of the Dragon: Anna May Wong’s Rendezvous with American History” (Liveright, 2023) is Huang’s third book in a trilogy of Asian American icons, including books on Siamese twins Chang and Eng and on Charlie Chan, both of which were National Book Critics Circle Award finalists. It has taken Huang 15 years to complete this series, telling what he describes as the epic journey of Asian Americans in the nation’s tumultuous history.

She performed in 60 films

“There was so much in that context that we can’t understand, but what we do see is that her iconicity survived decades,” says film scholar and filmmaker Celine Parreñas Shimizu, dean of the Division of Arts and distinguished professor of film and digital media at UC Santa Cruz, during a conversation with Huang at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art. Iconicity, she goes on to explain, is a term of reverence, used for a person who achieves so much in their lifetime that they attain “a kind of godlike status where we worship them because of what they were able to achieve.”

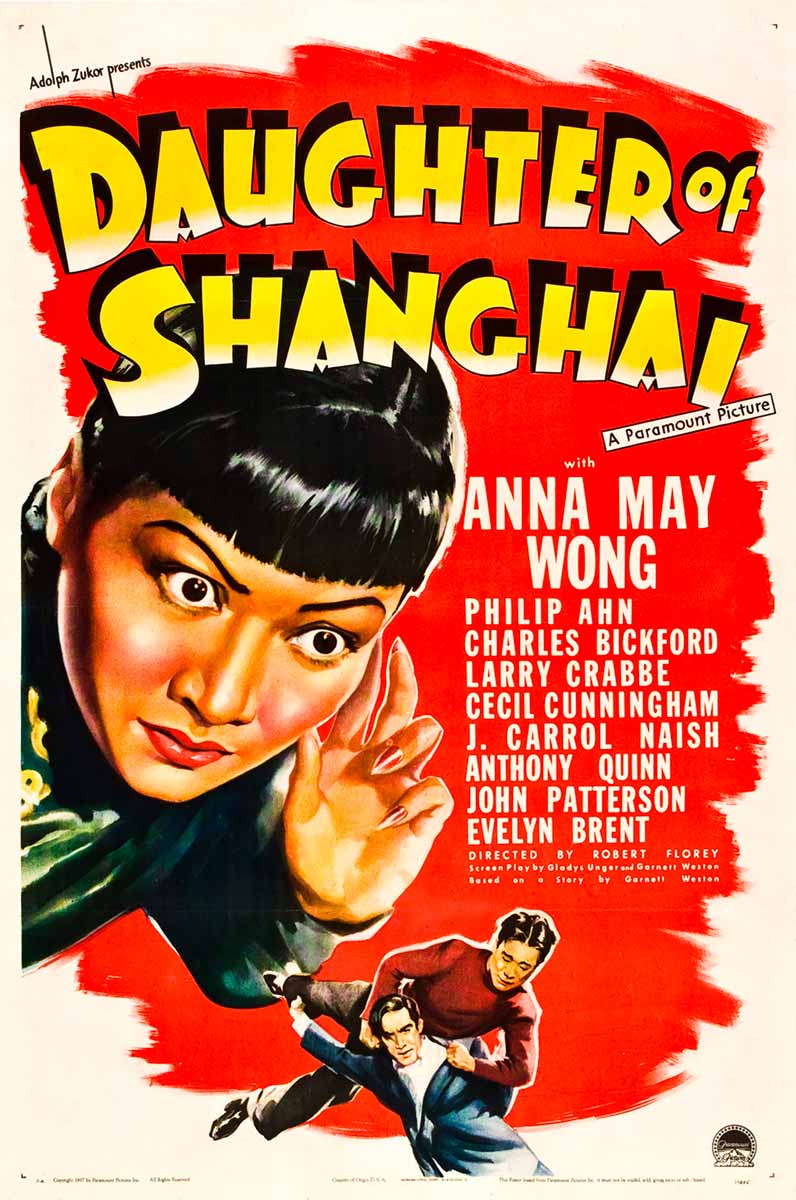

In her lifetime (1905–1961), Wong performed in 60 films, including the very first movie made in Technicolor. But in the decades since her death, she has been the topic of biographies, novels, films, TV series, magazine articles, videos and publications from film, media, literature, feminist and Asian American studies.

Today we would call her a maximalist. She was known for having the longest nails in Hollywood, author Anne Anlin Cheng writes in “Ornamentalism.” “This was not fake. She cultivated these nails. Every time she took on a job, she was like, ‘Do I have to cut my nails?’” says Parreñas Shimizu. But, at the same time, she notes, Wong also had risque costumes and other accoutrements of racial femininity, “deploying her heritage in this way.”

In her letters, Huang finds evidence that Wong knew what she was doing, sometimes telling friends, for instance, that she had to sacrifice her nails for a character, such as for “Daughter of Shanghai,” in which the director made her cut her nails for the part of a doctor. Huang relates the control over Wong’s body to what he’s learned from the Chinese community about suffering.

“Speaking of female beauty and pain, nothing is more torturous and painful than having your feet bound for the pleasure of the male gaze,” says Huang, whose grandmother had bound feet. “I came to Anna May Wong’s story through these personal, historical and cultural understandings and experiences.”