Charlie was here; and Joe was here; and somebody wrote, “Mom.”

In the late 1960s, people started hammering their names in nails on the wooden railroad ties near where artist Alex Lukas grew up in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He walked by the string of names for years, but it wasn’t until 2016, upon learning the old rail ties were being removed, that he returned to photograph them.

The photos became the source material for the first issue of Written Names Fanzine, Lukas’s publication dedicated to documenting and transcribing occurrences of hyperlocalized, unsanctioned public name writing. The latest issue features names stuck in bubble gum in San Luis Obispo.

“It’s about an appreciation and investigation into places where people gather, and places where people are interested in commemorating their time there by writing their name,” says Lukas, an assistant professor of publishing and printmaking at UC Santa Barbara.

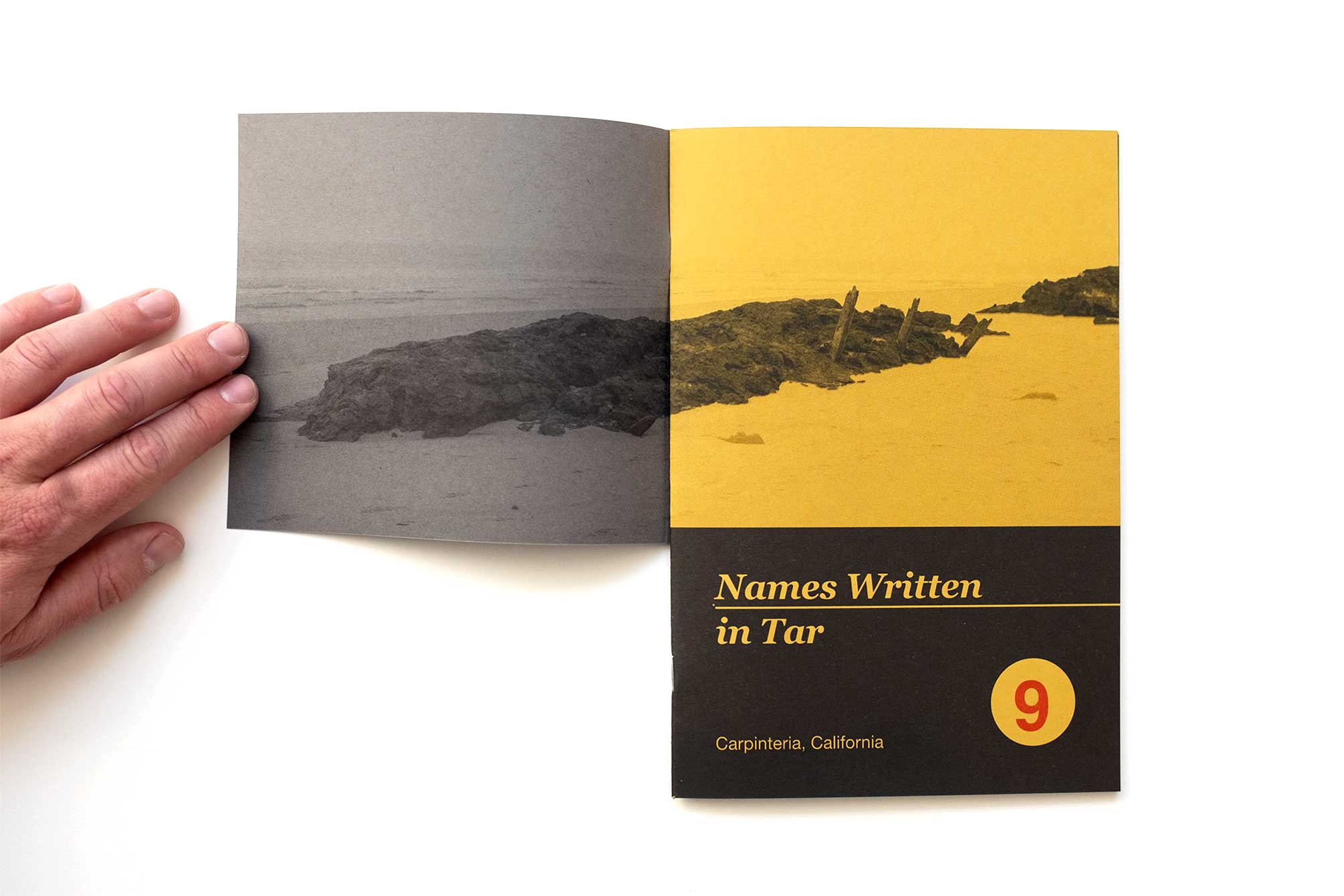

Through 12 issues, starting with the Cambridge nails, Lukas has explored names he’s found across the country: etched in aspen trees by sheepherders in Idaho’s Sawtooth National Forest; spray-painted on abandoned bicentennial-themed trolleys in Pennsylvania; smeared in beach tar on rocks in Carpinteria; scrawled in soot on Mammoth Cave’s Gothic Avenue in Kentucky; and carved into cacti at Enchanted Rock in Llano County, Texas; among other places.

As with the names that zigzagged across a roughly 20-foot section of the train tracks, it is often difficult to decipher if the geographically succinct clusters of names are from people who knew each other or if they are signatures of a spontaneous happening among strangers at different points in time. Without any intervention, Lukas photographs and transcribes the names for his fanzines.

For one issue, Lukas documented dozens of names spelled out in rocks outside Amboy, California, population 5. “It’s a ghost town but there are hundreds of names written in rocks along Route 66,” he says. “It was another iteration of people responding to a site. They’re pulling their cars over and there’s an engagement with the place and with its materiality.”

Fanzines, also known just as zines, are hard to pigeonhole. They emerged as early as the 1930s among science fiction fans. Their roots are informal, outsider and underground. Small run, self-published rags of counterculture, zines were created by political and social radicals of the 1960s and the punk rock circuit of the ’70s — then breaking into mass culture in the ’90s, as a subversive form of self-publishing.

“It’s a tradition of using the tools at hand to make publications that either nobody else will publish or you don’t want anybody else to publish,” Lukas says. “It’s a history of folks using photocopiers, right? It’s the experience of going to Kinko’s late at night when the person working the overnight shift was always some punk who was there to make their own zines.”

An assistant professor of print and publication arts, Alex Lukas works in his art studio in UC Santa Barbara’s Old Gym a.k.a. the Red Barn. Photo by Debra Herrick

It’s not lost on Lukas that he is following a tradition whose history intersects with the rise of the common copy shop; and the king of copies, Kinko’s, started as a print center in Isla Vista, serving UC Santa Barbara students. When the photocopier became an accessible tool, a new generation of zine-makers — including teenage Lukas in the late ’90s — were able to bypass the cost of offset printing and release titles with small edition sizes.

That potential for a low print run is important. “We (zine-makers) are making things that are for and about subcultures or niche interests,” says Lukas, who makes about 100 copies of each zine on a Risograph duplicator. “Because there aren’t a thousand people who are interested in this. It’s a small community where maybe a hundred folks want this stuff, but those folks are passionately interested.”

Lukas took partial inspiration for the design of Written Names from old national park guides. “Printed objects to help you navigate a space that you are visiting was the aesthetic cue,” he says.

At the San Francisco Art Book Fair and at the Los Angeles Art Book Fair, Lukas has presented Written Names among publications that span from $5 pamphlets to case-bound artist monographs.

“My publication sits somewhere in between,” he says. “That idea that it’s just folded and stapled paper is important to me, but they are also conceptual art objects.”