REDUCE, REUSE, REIMAGINE

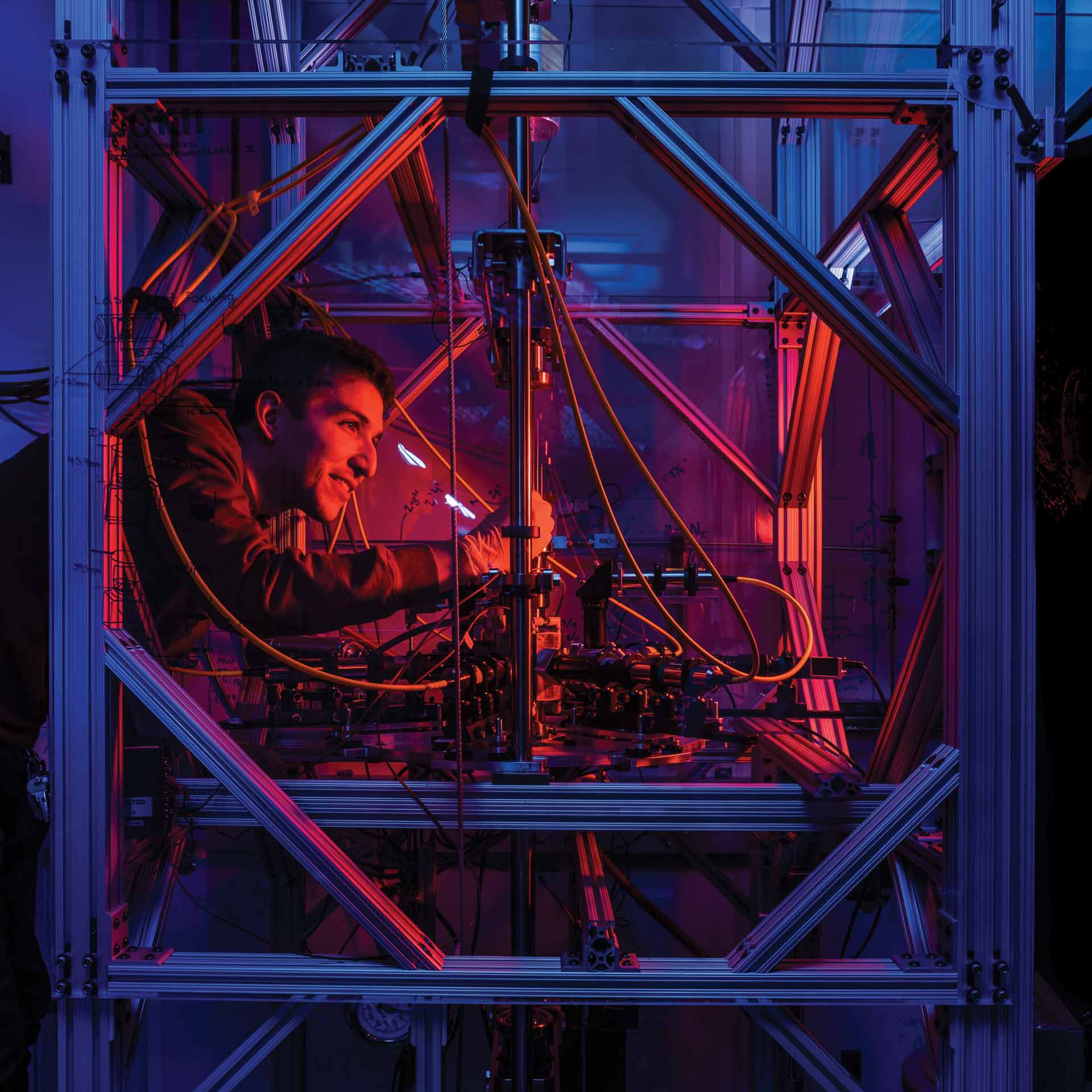

By reducing materials to their molecular components, we can produce recycled materials with the same properties as their virgin counterparts. Indeed, Scott’s group works on disassembling polymers — specifically polyethylene and polypropylene — into ingredients that can be returned to the supply chain. She’s even found processes where beginning with the recycled plastic is more efficient than starting from crude oil.

Technology alone won’t solve this issue, but it will be critical to our solution. “We need people to reimagine how we make things and how we use them,” Scott says, “but we also need changes in behavior.”

As long as resources are cheap, people will continue producing virgin materials. The standard argument is that circular practices are currently too expensive to compete with a linear supply chain.

“But this is thinking the wrong way around,” Geyer says. “It’s not that reuse and recycling is too expensive; it’s that virgin production is too cheap.”

Not only has society designed the modern supply chain around virgin production, but the prices of products reflect the true cost of these practices. Economists call these indirect impacts “externalities,” and the linear economy is rife with them.

Ironically, Geyer suggests that we shouldn’t focus on incentivizing circular practices. Rather, we need to disincentivize linear practices. You might think this is the same thing, but evidence suggests it isn’t. For instance, instead of discouraging the use of fossil fuels, a lot of governments are promoting renewable energy. “But this could mean that we’re just going to do it all,” Geyer says: “keep our fossil fuels and use a lot of renewable energy as well.”

Similarly, if recycling becomes cheap, we may just use it alongside virgin material. “The green revolution has been a double-edged sword,” he says. “It basically allowed us to not talk about limits and just expand.”

To do less harm, we need to curb our worst practices, not promote our best ones, Geyer argues. Ultimately, this means producing less overall.

Rappaport’s historical perspective leads her to a similar conclusion. Consumption is inexorably linked to people’s working lives. As specialization and work hours expanded, people were left with less time, energy and skills to reduce, repair and recycle. “You have to slow things down,” she says.

“Overall, there’s no one strategy that’s going to solve the whole problem,” Scott adds. “But I think the world is ready to start thinking about this in ways that we weren’t even five years ago.”