Atop a 1,740-meter peak in the San Gabriel Mountains above Los Angeles, on land first settled by the Indigenous Tongva peoples, is the Mount Wilson Observatory, where throughout the 20th century some of the world’s biggest telescopes helped lead men — primarily of Western European origin — to monumental discoveries. At Mount Wilson, founded by George Ellery Hale in 1904, Harlow Shapley figured out the size of the Milky Way and Edwin Hubble calculated the distance to Andromeda.

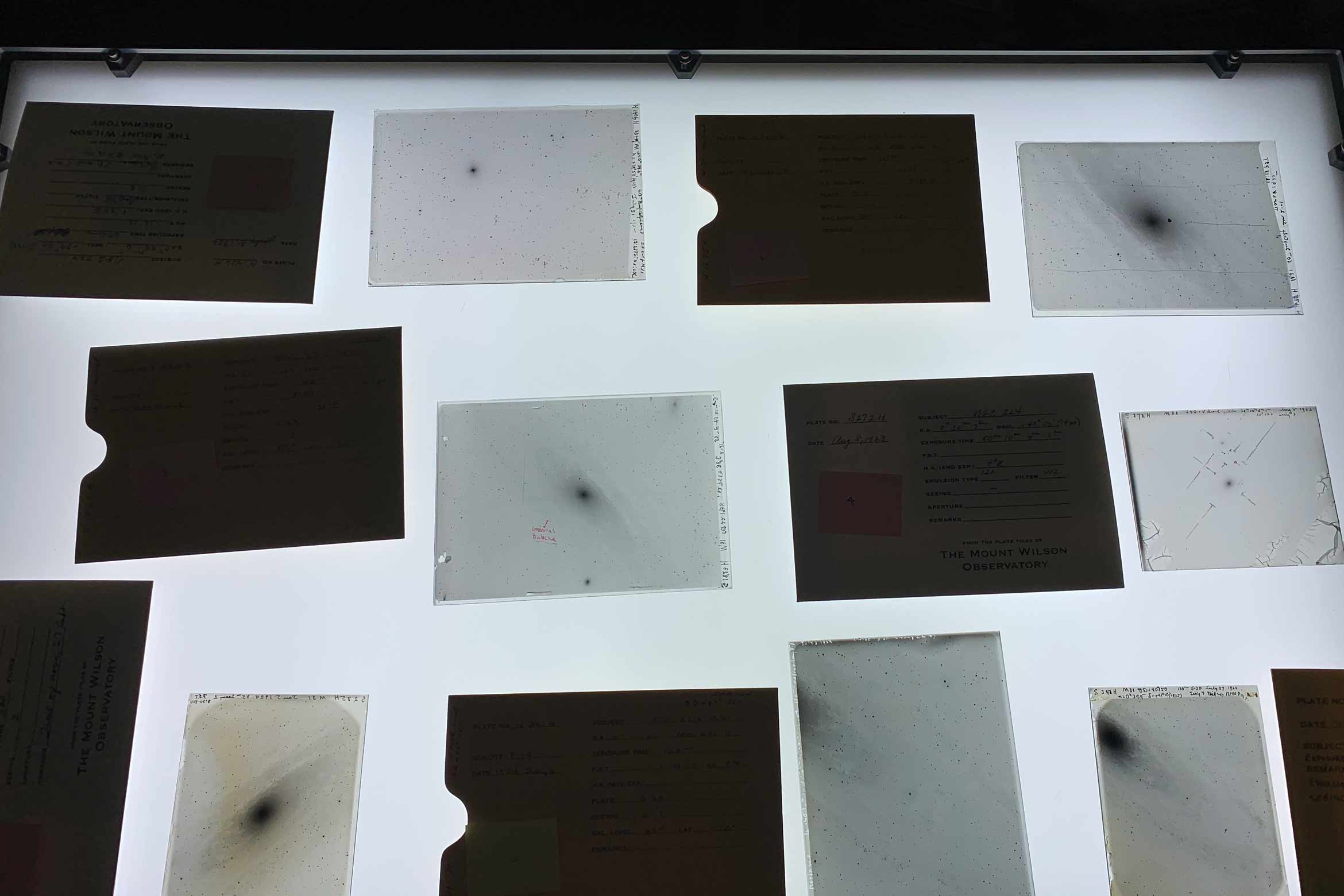

Throughout Mount Wilson’s early history, women worked there as data scientists, often called “computers.” Female computers meticulously charted and cataloged the changing coordinates of stars over time, recording their positions and light from glass plates — an early capture medium of photography.

Much of the shimmering starlight collected by women and recorded on glass plates — at once early data used to illuminate our place in the universe and time capsules of the stellar past — is now out of reach to observers, as Los Angeles’ light pollution has obscured its presence in the night sky.

Glass plates that provided inspiration to Rosalena's art. Courtsey photo.

The glass plates, today a part of the observatory’s archival collection, are now also the subject of “Standard Candle,” an interdisciplinary research project by artist Sarah Rosalena, who is reexamining labor conducted by female computers at Mount Wilson.

Producing Indigenous weaving and beading based on data sets from the glass plates, Rosalena proposes a hybrid language, emphasizing the female computers’ hidden labor and acknowledging that Indigenous cosmovisions predated the Mount Wilson telescopes.

“It was a way of capturing light materially — on glass plates — and whatever they’ve captured is tied to a sense of place, as stars are grounded to a physical location and time,” says Rosalena, an assistant professor of art. “Not only was the light that was coming through the telescope only happening at that exact moment, but it is absolutely irreplaceable due to light pollution, including the devaluation of Indigenous knowledge and female labor.”