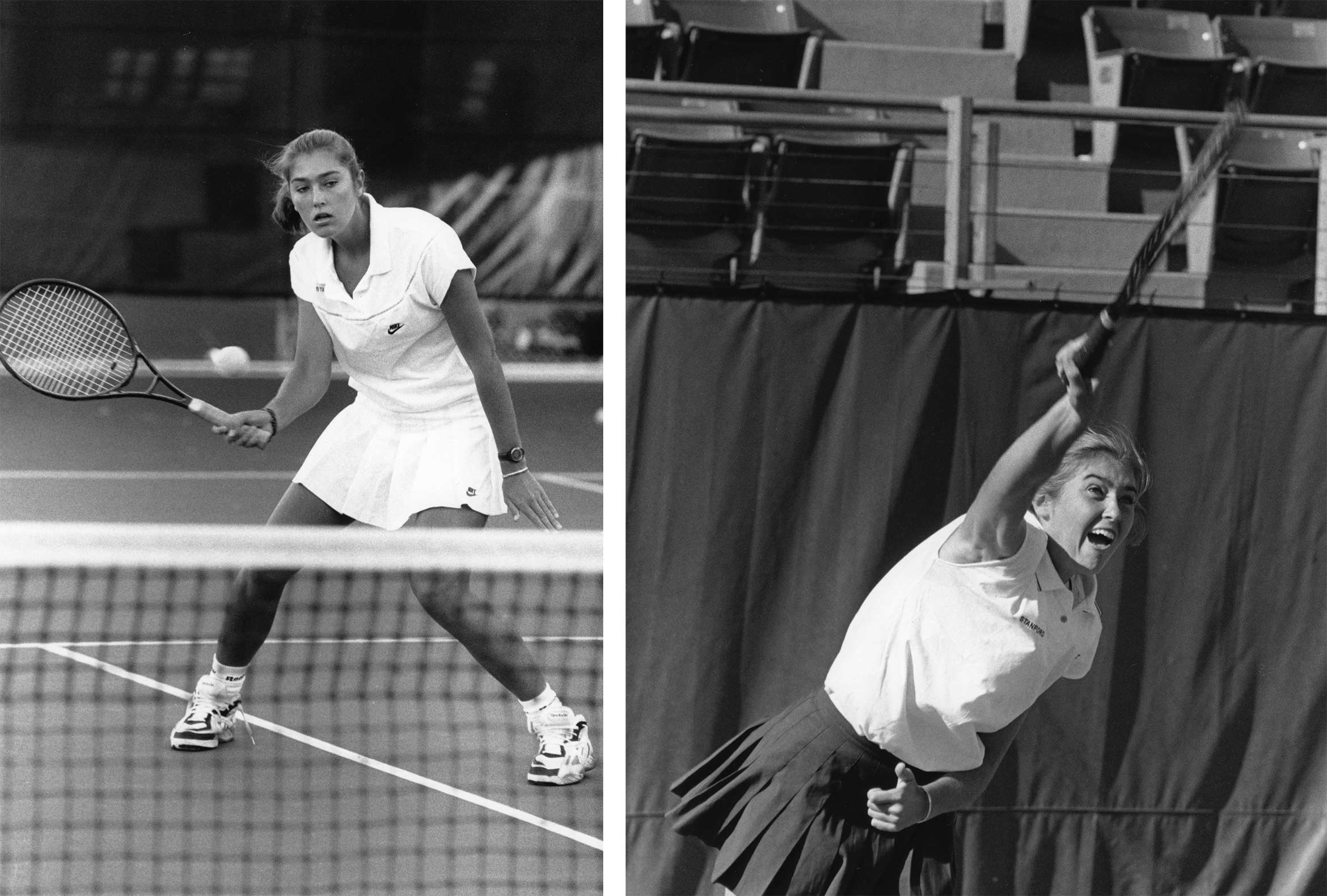

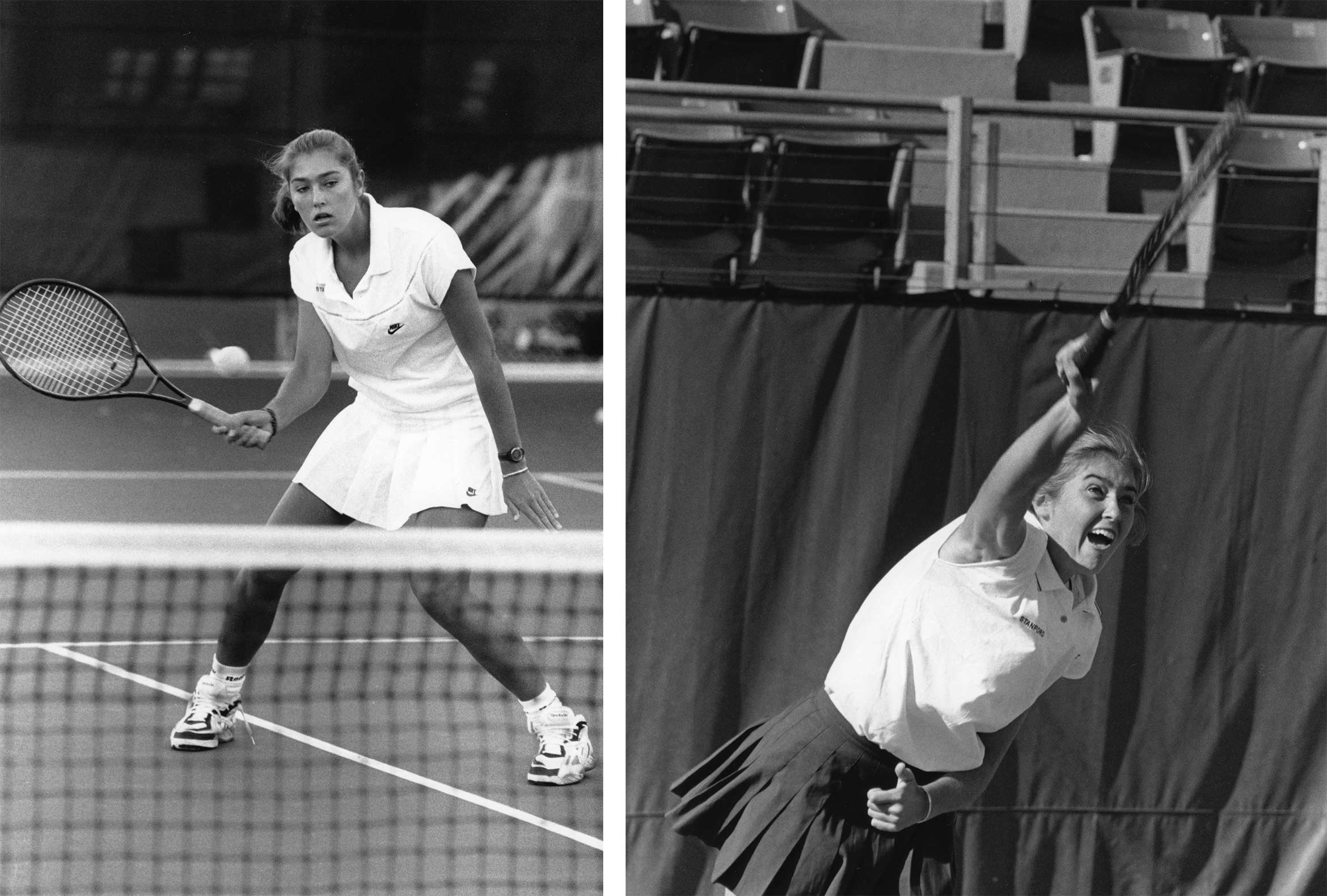

Ania (Bleszynski) Jayich on the court for Stanford

PHOTO BY STANFORD ATHLETICS

Ania (Bleszynski) Jayich on the court for Stanford

PHOTO BY STANFORD ATHLETICS

A former tennis prodigy, Ania Jayich brings the same grit and focus to physics that once powered her athletic success

by Nora Drake

Ania Jayich has an athlete’s mindset when it comes to scientific innovation. She describes her competitive drive as inherent and internal, something that has motivated her for as long as she can remember. “Some of the things that drive me are, ‘I want to be the first one that does this,’ or, ‘I want to do it better,’” she says. “I think I was born a competitive person, and I try to leverage that in a positive way.”

A professor of physics at UC Santa Barbara and co-founder of the interdisciplinary Quantum Foundry, Jayich qualifies her ambition by noting that she doesn’t let it get in the way of successfully working with other researchers. “I think the way that I behave doesn’t reflect my competitive spirit, necessarily,” she says. “I have many collaborations.” It’s no surprise her drive carried her into academia; after all, she once held the No. 1 national ranking for women’s 18-and-under singles tennis.

Jayich’s parents were also physicists, who prized academics over athletics and were not shy about sharing their values — which meant sometimes having to make tough choices and have difficult conversations. “Growing up in my household, there was no way that I was going to be sacrificing anything academically for tennis,” she says.

Far from pushy sports parents living vicariously through their children, her mother and father were mostly disinterested in her athletic abilities. She recalls one match in Ojai in particular. It was one of the few chaperoned by her dad, who generally preferred to leave those duties to her mom.

“After the match, I walked up to him,” she says, “and he was like, ‘So, how did you do?’” (She won.)

Jayich reached a crossroads when she was 18 and ranked No. 1 in the country: Go pro or play in college? She dipped her toe into the pro lifestyle by traveling to a few tournaments. “I distinctly remember feeling like, ‘This is not for me. I like it, but not this much,’” she says. “I realized at that point that the girls on the pro tour were very different from me. I didn’t feel like I fit in.”

Ultimately, she decided to attend Stanford University, which had both a top tennis team and a stellar academic reputation. She received a full scholarship that allowed her to take six years to complete her degree, so that she could double major in mathematics and computational science and in physics while still attending practices and traveling with the team. Her team won the NCAA team tournament in her junior year and she made it to the NCAA individual finals her senior year.

Again, she thought briefly about going pro. “At the time, the good female collegiate players were not really making it on the pro tour after college,” she explains. “I mean, a lot of them played on the tour, but you weren’t going to be in the top five.” She knew it wouldn’t be enough for her. She decided to transition to full-time academics.

Jayich got her Ph.D. at Harvard University, while volunteering as an assistant coach for their tennis team to stay involved in the sport. She considers herself lucky to have made it from age seven to age 24 playing a demanding sport and never experiencing any significant burnout. Her ambition never wavered. “I think it’s also because if I wanted to quit, my parents would have been super happy about it,” she says wryly. “My drive came from within.”

Not that she never experienced moments of doubt. “A couple of my friends did keep playing after college,” she says. “When I was in grad school, a good friend from Stanford was playing the tour and living in Boston, so I saw her life up close. She’d get up in the morning, eat some protein-filled breakfast, then she’d go work out for three hours, eat, lift, play tennis again, etc. Somehow, I missed that part.”

She remains grateful to the sport for teaching her skills that she still uses in her career, like time management and the importance of hard work. “To be good at something, you have to work hard and you have to train,” she says. “And it’s not always easy, and it’s not always fun.”

Now, Jayich works to discover quantum phenomena to create highly sensitive sensors from engineered defects in diamonds, with the goal of being at the cutting edge of imaging the atomic structure of individual proteins. There are many days that are neither easy nor fun.

“Our group works on developing quantum technologies or realizing quantum mechanical phenomena and controlling them,” she says. “We’re trying to build sensors that could be applied to imaging biological systems or new material systems. The real-world application would be, for instance, imaging the structure of a protein with high spatial resolution magnetic resonance imaging or performing high throughput proteomics.”

Ania Jayich with her daughters at the UCSB Rec Cen

Photo by Matt Perko

When she’s not in the lab, Jayich supports her three children in their burgeoning tennis careers (unsurprisingly, they are quite good), often helping them warm up before practices and matches. Ever her parents’ daughter, she is careful to remind them that school is still more important than sports.

In addition to preparing her to parent scholar-athlete children, Jayich says that the most important thing tennis taught her was how to lose.

“It made me resilient,” she says. “Early in my career, I would get grant proposals denied and it just bounced off of me. You lose a lot in tennis. So in my life now, if something doesn’t work, it doesn’t stop me. I think I have a pretty healthy approach to failure.”