On a hot summer’s evening, E. Philip Pister found himself carefully navigating a desert wetland, alone in the fading light, carrying two heavy buckets full of tiny fish — the totality of the world’s Owens pupfish.

Finding a bigger bucket

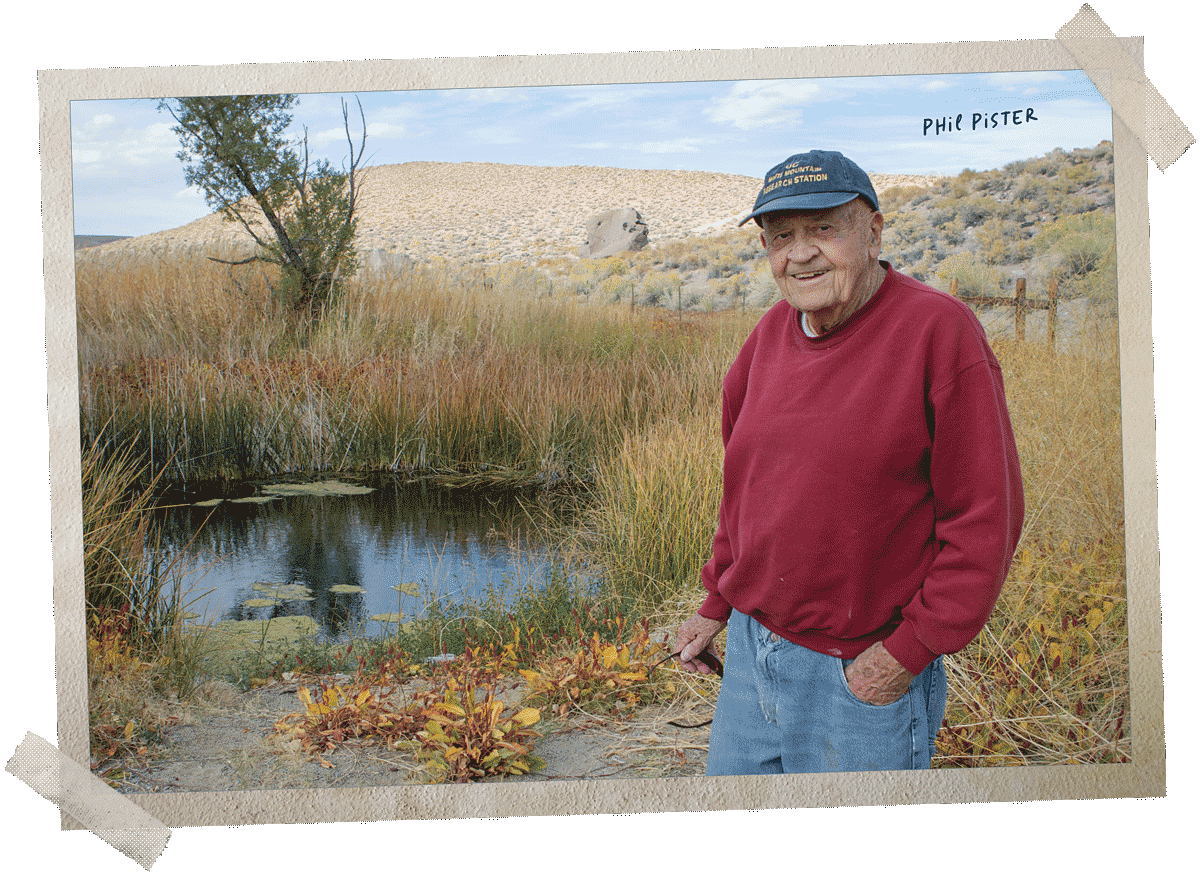

While Pister was best known for single-handedly rescuing the Owens pupfish that fateful evening in 1969, his true legacy stems from more than a half century pioneering a change in American ideology from mere resource management to a true environmental ethic.

Upon his passing in January 2023, the veteran fishery biologist left his entire collection of books, slides, research papers, field notes and awards in the care of UC Santa Barbara’s Sierra Nevada Aquatic Research Laboratory (SNARL), a site he shared a history with. The university is now working to catalog and digitize some of these resources to support research and conservation in the eastern Sierra and beyond.

Certainly, the endeavor to revitalize the region’s rare endemic fishes is ongoing. Not two miles away from the newly appointed Pister Library at SNARL is the last natural habitat of the Long Valley speckled dace. This small fish, and others like it, used to populate many of the area’s rivers and ponds. Pister’s slides and notes will provide invaluable insights for staff at the California Department of Fish and Wildlife working at UCLA’s White Mountain Research Center to restore dace populations. That is, if they can find another home for these fish in the first place.

Photo by Elaine Miller Bond

A career devoted to management and conservation

Throughout his life, Pister blended strong values with scientific knowledge to champion the field of environmental ethics in eastern California. His calling was to learn how humans can thoughtfully interact with the natural world and make decisions based on our best knowledge. He spent 37 years at the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW), primarily managing fish populations in eastern California and the ecosystems they inhabited.

Born and raised in Stockton, Pister spent many summers during the 1930s with his family in Tuolumne Meadows, where he gained an appreciation for the eastern Sierra. He entered UC Berkeley intent on studying medicine, but a “timely nudge from his older brother Karl acquainted (him) with an exciting young professor named Starker Leopold, who was just then introducing a bold new curriculum called ‘Wildlife Conservation,’” Pister’s longtime friend Frank Baldwin recalled at his memorial service. “Phil took to it like a trout to a fly.”

A. Starker Leopold was the eldest son of famed naturalist and conservationist Aldo Leopold — author of “A Sand County Almanac” — and a luminary in his own right. The younger Leopold left a lasting impression on his student: Environmental ethics would guide Pister’s work as a fishery biologist, and he continued speaking on humankind’s moral obligation to the natural world well into his 90s.

Pister conducted his thesis on the Convict Lakes Basin at SNARL in the 1950s, when it was still the Fish and Wildlife Service’s Convict Creek Experiment Station. “I think SNARL was near and dear to his heart,” said reserve director Carol Blanchette, “and he felt that SNARL would be an appropriate place for his long-term archive.”

Indeed, he was instrumental in transferring the research station to UCSB when the federal government planned to close it in the early 1970s. “Phil was the one who called me when he heard that SNARL might become available at a discount price of $1 if we would be interested in acquiring the facilities,” recalled Roger Samuelsen, the founding director of the UC Natural Reserve System and one of Pister’s close friends.

The opportunity arrived just a year after a large parcel near Mammoth Lakes was donated to the Natural Reserve System, in the care of UC Santa Barbara. Since the Convict Creek Experiment Station was a mere 20 minutes away, UCSB seemed the natural place to administer this new reserve.

“He really believed in SNARL; he really believed in the Natural Reserve System, and he wanted to do everything he could to encourage our success,” said former SNARL director Dan Dawson.

The Pister Library

Pister’s career spanned over half a century, and he continued advocating for environmental stewardship to his final year. Late in life, he, his children and Samuelsen began to discuss where to donate his extensive collection. Unfortunately, they hadn’t solidified any plans before Pister passed away. While he had previously provided interviews for the Oral History Center at UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library, finding a repository for his personal and professional effects was another matter.

“When Carol Blanchette was so receptive to the library being at SNARL, to remembering Phil, and to hosting the memorial service, it just became clear that it was the right home,” Samuelsen said.

The UCSB Library will digitize his slides — which number more than 24,000 — to make them more accessible to researchers, resource managers and the public. Blanchette and Samuelsen would also like to digitize Pister’s field notes, if the team can find the funding.

“Phil kept copious notes on almost a daily basis throughout his career,” Samuelsen said.

Indeed, the collection is a regional treasure trove, and its transfer to SNARL will ensure that it remains accessible to researchers and professionals in eastern California. That's a real boon for a rural area where there's typically not a lot of redundancy in the system. A single person is often the sole keeper of a lot of records.

“Phil really was ‘the desert fish guy’ for a long time,” said environmental scientist Nick Buckmaster, supervisor of CDFW’s Inland Deserts Fisheries division. “Phil’s records, the photos and the notes that he has, are sometimes the only records that exist of how things used to be.” They’re a windfall for scientists seeking to understand how the region has changed.

Fish in the desert

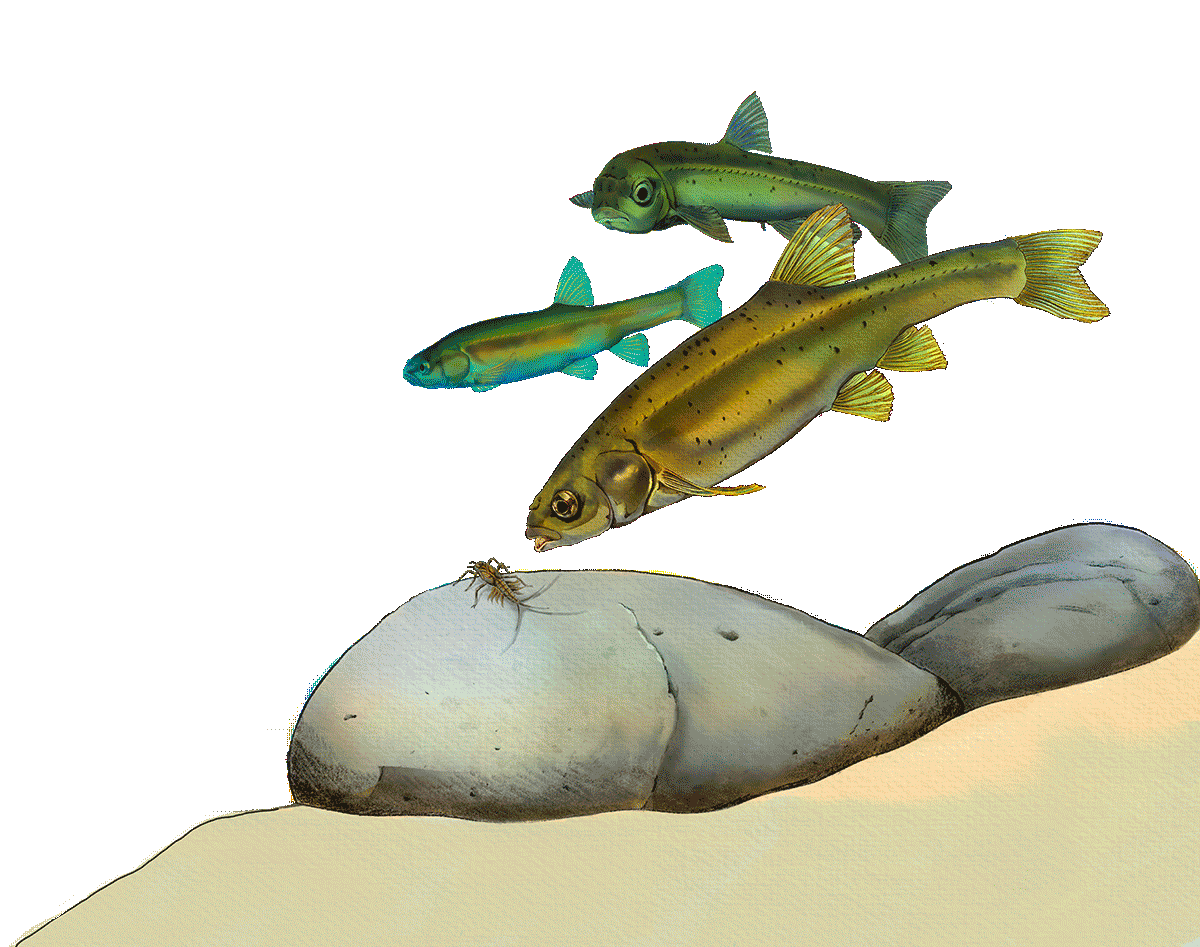

The eastern Sierra and California deserts may seem a peculiar place for a fishery biologist to make a career, but the region contains an unexpected diversity of unique aquatic species, relics from its wetter past.

Over the last 4 million years, eastern California has experienced climatic changes and repeated earthquakes that reshaped its geography. The region once hosted a network of lakes, which enlarged and connected during ice ages and receded and disconnected during interglacial periods. This dynamism produced times when fish were alternately dispersed and isolated, eventually sending different populations down separate evolutionary pathways.

Many of these fishes evolved in isolated habitats and became integrally tied to the health of their small ecosystems. “Even though they might be three inches long, they were the apex aquatic predators in their habitats,” Buckmaster explained.

Pupfish savior

As a fishery biologist with CDFW, Pister worked on a variety of projects, from keeping sports fishermen supplied with trout to preserving the integrity of isolated desert springs. And working in eastern California placed a dramatically diverse territory under his charge: “If I left the roadhead near the base of 14,494-foot Mount Whitney at 9:00 a.m., I could make a leisurely drive to the east and have my lunch 282 feet below sea level on the floor of Death Valley,” he once wrote.

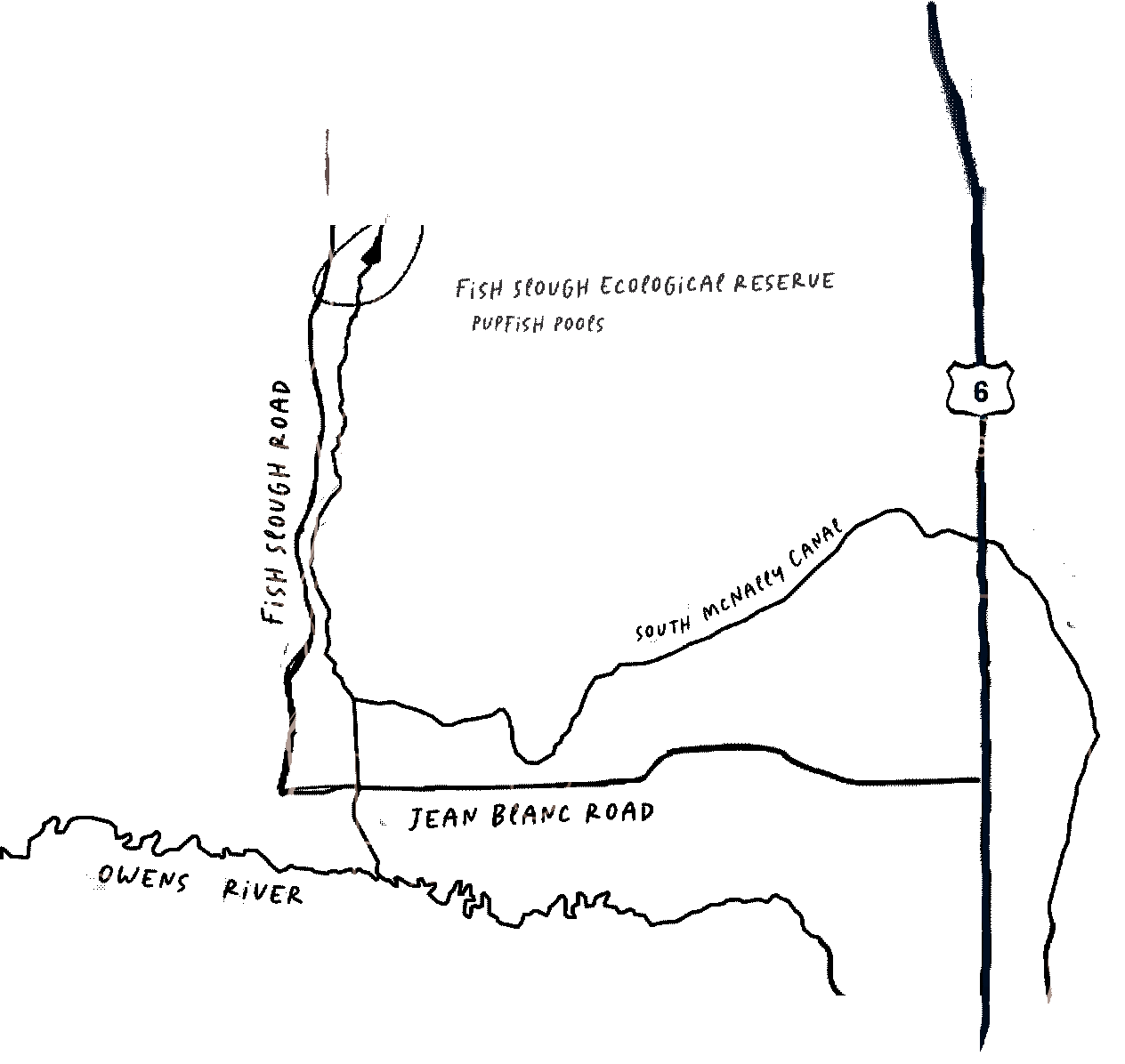

Aug. 18, 1969, stands out from the many entries in his yearly diaries — now all a part of the collection at SNARL: “Transplanted Cyprinodon at Fish Slough; purchased alkaline D-cells, $2.00.” This succinct note summarizes his great rescue of the Owens pupfish.

Millions of these fish had once thrived in the vast marshlands of Owens Valley. By 1942, land use changes and the introduction of predatory game fishes had seemingly driven them to extinction. Pister had actually helped rediscover the species in 1964, when he, along with ichthyologists Robert Rush Miller and Carl Hubbs, found a few hundred individuals holding out in a single pool in the Fish Slough marsh.

Recounting the episode years later, Pister said: “It was almost completely dried up when an alert assistant came into my office and announced: ‘Phil, if we don’t get out to Fish Slough immediately, we are going to lose the species.’ His pronouncement was no exaggeration. It was the hard truth!”

They rushed toward Fish Slough with nets and aerators and removed the remaining 800 survivors. The team secured the fish in wire-mesh cages in one of the slough’s main channels, and planned to move them later to safer locations. Pister then stopped for dinner while his teammates returned to town. He checked on the pupfish one last time before departing for the day.

It was a disaster. In their haste, the biologists had placed the fish away from the main current. By the time Pister realized, many of the fish had begun to suffocate for lack of oxygen. With daylight in short supply, Pister recognized he had to act immediately. He sprinted to the truck, dropped aerators into the two buckets he had left and began walking the species to safety. He later wrote about it in his essay, “Species In a Bucket”:

Although the passage of time has obscured my exact words and thoughts as I lugged two heavy buckets and their precious cargo (each weighing more than thirty pounds) over the treacherous marsh terrain, I remember mumbling something like: ‘Please don’t let me stumble. If I drop these buckets we won’t have another chance!’ I distinctly remember being scared to death. I had walked perhaps fifty yards when I realized that I literally held within my hands the existence of an entire vertebrate species. (American Currents, Vol. 40, No. 3)

Once at his truck, Pister was able to drive the totality of the world’s Owens pupfish to deeper water on the far side of Fish Slough.

A champion of native fishes

Aug. 18, 1969, was a particularly dramatic day in Pister’s career, but the great good he did comes from decades of relentless support for the delicate ecosystems under his care, and the unique species that evolved within them. “People always associate Phil with things like pupfish,” said CDFW supervisor Buckmaster, “but Phil was instrumental in keeping the golden trout, California’s state fish, alive.”

Conservationists laud Pister as a father of native fish restoration in America. He co-founded the Desert Fishes Council, an international scientific and advocacy society; he testified before the Supreme Court to protect the Devil’s Hole pupfish; and he worked to remove non-native fish in Nevada and protect native fishes in Mexico. He broadened the conversation around rare fishes in the eastern Sierra and the deserts, expanding management beyond game fish to a more holistic stewardship. It was a shift that coincided with large-scale changes in America’s environmental psyche.

“What Phil did was of immense consequence,” Buckmaster said. “And it’s important to consider that in light of the times: this great awakening in American society to the value, the intrinsic value, of these resources and these species that up until then had been viewed as an impediment to progress.”

“His message is that we have a responsibility to take care of these species,” said reserve director Blanchette. It’s a principle that still guides the people and agencies that carry on Pister’s work.

Photo by Elaine Miller Bond

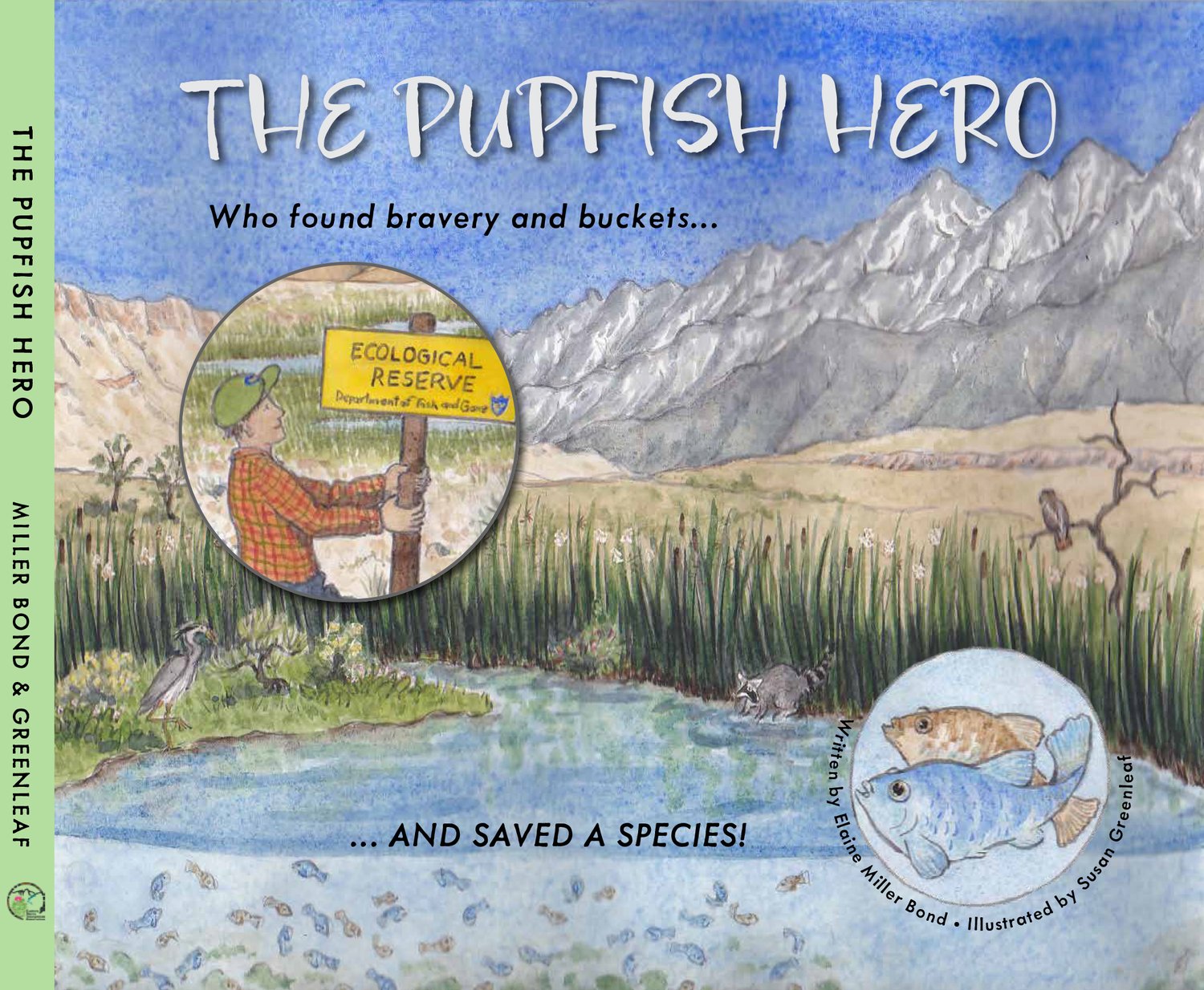

Teaching people to care

Although he was naturally a humble man, Pister’s pupfish rescue has been memorialized in articles, books and videos. He was even the star of a children’s book, “The Pupfish Hero.” But few people appreciated these fishes at the time. “My mother’s childhood friends used to make fun of Phil for what he did,” said Gaylene Kinzy, a staff member at UCLA’s White Mountain Research Center who grew up in the nearby town of Bishop.

It’s understandable why. Many of these fish are small and inconspicuous, and the effort to rehabilitate them and other endemics continues to face issues and resistance. Many landowners have honest concerns about the impact that protected species will have on them and their properties, Buckmaster explained. Unfortunately, this has led to populations of small fishes surreptitiously disappearing in the past.

“People often asked Phil this question: ‘Oh, you study the desert pupfish. What good is a desert pupfish?’” Blanchette recounted. “Phil’s answer, verbatim, would be, ‘What good are you?’”

More than just a tit-for-tat, Pister’s response really asked people to consider why we decide to value a species — or an individual for that matter — whether a pupfish or a human being. In the case of desert fishes, these species are as unique as Darwin‘s finches in the Galapagos. Each species diverged from its neighbors as it adapted to the conditions in its own habitat over thousands of years of isolation — only instead of rocks and islands in the ocean, it’s creeks and springs in the desert.

Swapping fishes at White Mountain Research Center

For instance, consider the Long Valley speckled dace, a fish the size of a minnow whose only natural population lives a mile and a half from SNARL. The true future of this species lies 45 minutes to the southeast, where 95% of the population exists in a tarpaulin-lined pond at UCLA’s White Mountain Research Center (WMRC), one of SNARL’s sister sites in the UC Natural Reserve System.

The ponds were part of an ambitious project in the late 1980s and early ‘90s by UC Berkeley graduate student June Mire, now the director of ecological services at Tetra Tech, a Fortune 500 environmental consulting firm. The young biologist had met Pister during her master’s studies in New Orleans. His sincerity and charm soon converted her to the cause of threatened desert fishes, and she embarked on a doctoral program at Cal.

Owens pupfish were only present in two locations at the time, so Pister and Mire were concerned about the security of these habitats. She hatched the idea to create an emergency refuge for the species. “Everybody wanted this work to be done, and I was crazy enough to do it,” she recalled. Part of her aim was also to learn what these fishes needed in order to thrive. So she designed the three fish refuges to support controlled experiments.

The Owens pupfish had been officially listed as an endangered species for some time by 1989, which provided research and conservation funding for the project through CDFW. Still, construction was a massive undertaking. “White Mountain Research Center was incredibly supportive of my work,” Mire said. “They gave me space, labor, storage, everything I needed to do this.”

Jump to around the year 2000, and Phil’s successor, Steve Parmenter, was dealing with a newly discovered lineage of Owens tui chub. Although Mire’s ponds were overgrown and in disuse by this point, it was a simple matter to revitalize them and rekindle the relationship between White Mountain and Fish and Game to provide a refuge for this endangered fish.

The quick collaboration proved crucial, because, not two years after its discovery, the original population of tui chub had vanished under dubious circumstances, with dry ponds and stocked fish left in their stead.

In late 2020, Parmenter and Buckmaster converted one of the ponds into a refuge for Long Valley speckled dace, hosting fish gathered from the last population near SNARL. The hope is that the team led by Parmenter’s successor, Buckmaster, will be able to introduce these dace into other suitable habitats at some point in the future.

The challenge of rehabilitating endemic species

According to Buckmaster, these rare endemic fishes face three existential threats. The first is habitat loss. “Fish need water; they need habitat,” he said. “And when they only occur in a small area, it’s very easy to lose it.” This is especially true in California, where vast infrastructure projects have rerouted water across the thirsty state.

Secondly, these species are no longer the big fish in their little ponds. Humans intentionally introduced popular game fishes — such as largemouth bass and rainbow trout — and other invasive species, like the red swamp crayfish. The eastern Sierra didn’t really have any large predatory fishes that could colonize the region in the distant past. After so long without a predator, these small endemic fishes are now easy prey for non-native species.

Lastly, these little fish make great bait. So when a fisherman brings baitfish from one watershed into another, interbreeding can reduce the distinctions between species. “With hybridization, you lose the evolutionary history of that species; you erase it,” Buckmaster said. So while there may still be pupfish, chub or dace in a stream, they’re no longer the same fish as their ancestors.

Many of these fishes also used to range throughout eastern California. “Pupfish used to number in the hundreds of millions,” Parmenter said. “They were all over the Owens Valley and in the Owens River.” But once people began stocking bass and trout, the places these native species could survive shrank to only the area’s isolated ponds and springs.

Such is the circumstance of the Long Valley speckled dace. “The only thing we don’t have is a place to put these fish,” Buckmaster said as he walked toward their pond. “So they’re just kind of homeless.”

Parmenter concurred: “With habitat that small, you can’t set up a conservation scenario and then walk away and expect it to be self-maintaining.” In that sense, these species now rely on our continued management, because many of the issues humans have created are here to stay. Even if one could remove all of the bass and non-native trout, it would only last until the next avid angler dropped a few back into a creek.

In that light, WMRC has become part of a larger network of native fish sites throughout the eastern Sierra and Owens Valley. “Unfortunately, we never really stopped managing them in buckets,” reflected Buckmaster. “Now the buckets have become small ponds, and we play a shell game to keep them alive.”

Environmental ethics and the moral imperative

Ironically, Pister and SNARL share some responsibility for the hardships these fishes now face. CDFW was not set up to worry about things like pupfish when Pister carried out his iconic rescue in 1969. “(They’re) no good to eat, and people don’t want to catch them, and won’t buy licenses, which is what we (were) interested in,” he said in an interview.

“It was my job as a California Department of Fish and Game aquatic biologist to provide good angling in the eastern Sierra recreation area for millions of people in Southern California, primarily through the stocking of large numbers of hatchery-reared rainbow trout — a species foreign to eastern Sierra drainages,” Pister wrote in an essay in the anthology “Moral Ground: Ethical Action for a Planet in Peril” (2011 Trinity University Press).

As a matter of fact, the initial purpose of the Convict Creek Experiment Station was to understand the success of hatchery-reared trout in native streams. “SNARL’s whole reason for being was to develop this fishing industry,” Blanchette explained. No one knew at the time how destructive non-native predators could be to these isolated ecosystems. And it seems Pister recognized the consequences of this naïveté early in his career. “Now a big focus of the research here is understanding the impact that those introduced trout have had on these native ecosystems.”

Pister’s values and education promised to make his job politically and philosophically difficult. “However, for my entire 37-year career, I was lucky enough to live and work at least 300 miles from my nearest supervisor,” he recounted in his essay, tongue in cheek. “This allowed me much freedom of action.”

Humans have had profound impacts on our surroundings. We alter the course of events that have taken millions of years to develop. “I feel we have a moral imperative to try to correct and mitigate the impacts that we’ve had on the environment,” Buckmaster said, echoing sentiments first developed by Aldo Leopold, then championed by his son Starker, and taken up by Pister.

Throughout the years, humanity has slowly begun to recognize the importance of preserving the integrity of natural systems. America has enacted laws mandating various environmental protections. Representatives of the American people convened and decided that these rare species are worth saving. “We’ve got three lines of reasoning to save these animals: the ecological imperative, the moral imperative and the democratic imperative,” Buckmaster said. “There’s meaning to be drawn from any one of those, and we really should respect all three.”

Buckmaster’s predecessors would likely be proud of the young biologist’s conviction, and the work he and those at the UC Natural Reserve System continue to carry forward — because carrying forward is precisely what Pister would implore of us. “In a very real sense, we and all our planet’s life-forms are slopping in two buckets while wild and poorly understood forces carry us into the future,” Pister wrote as he concluded his essay. “The warnings have been sounded, but will we respond soon enough, and with urgency sufficient to the work?

“There are no Fish and Game trucks and aeration systems waiting at the end of the trail to save us,” he wrote. “We must do that work ourselves.”

Read the book

The Pupfish Hero: Who Found Bravery and Buckets...and Saved a Species

Written by Elaine Miller Bond, Illustrated by Susan Greenleaf