Tucked away in California’s high desert is an elusive bird whose fate is tightly bound to its particular habitat. The greater sage-grouse lives in, nests among and eats its namesake plant: sagebrush.

“The health of the sage-grouse population is inextricably linked to the health of the sagebrush ecosystem,” says Carol Blanchette, director of UC Santa Barbara’s Valentine Eastern Sierra Reserves in Mammoth Lakes.

UCSB’s Sierra Nevada Aquatic Research Lab (SNARL), part of that reserve, is the operations base for researchers monitoring the southwesternmost population of this charismatic bird and changes happening to the sagebrush ecosystem. This work has enhanced our understanding of the species and informed conservation efforts along the California-Nevada border.

Balloon chickens

The greater sage-grouse is a rather plump fowl, about the weight of a domestic chicken, but with a build closer to its relative, the turkey. “Their whole lives revolve around the sagebrush: They nest in it; they eat it; and they live in it,” explains Camden McMillan, a research technician with the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). As a result, studying the grouse is a great way to understand the health of the ecosystem as a whole.

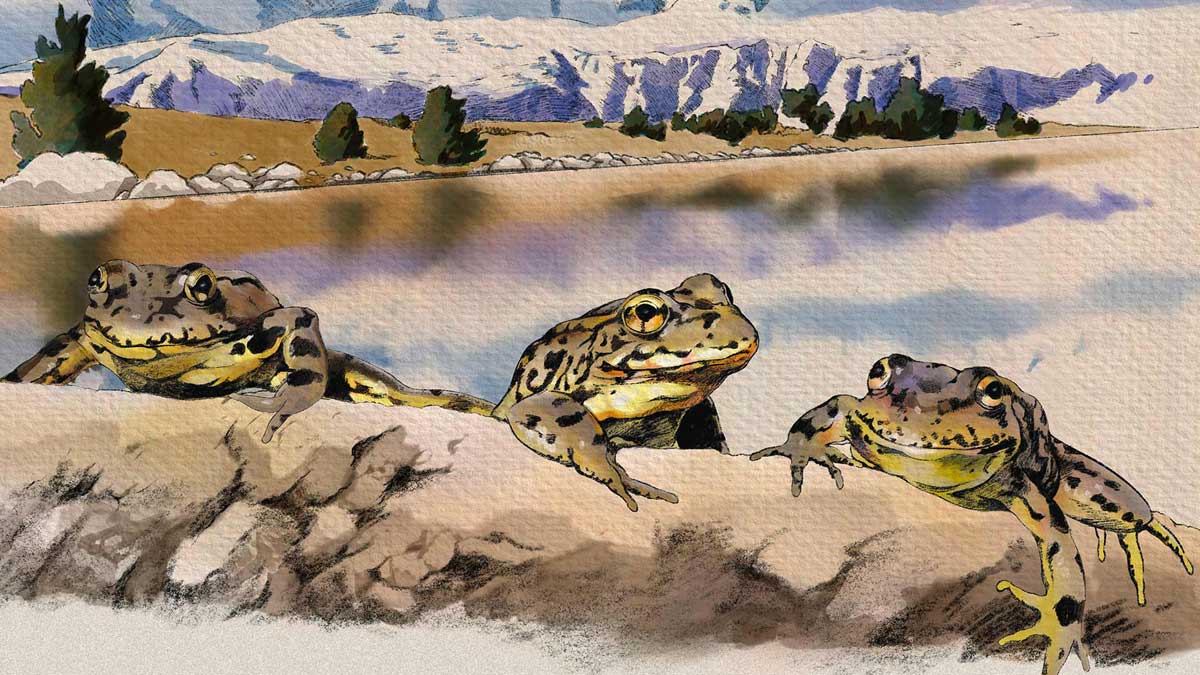

Indeed, the birds’ range mirrors that of the Great Basin sagebrush, stretching south from Saskatchewan to the extreme north of Arizona, and the western edge of the Dakotas to eastern California. Most populations intermingle, but a combination of mountains, human settlement and range restrictions has caused the population in the far southwestern limit of the species’ range to become isolated. Scientists refer to this region, spanning the California-Nevada border, as the bi-state area. The bi-state population has two strongholds: Bodie State Historic Park and the Long Valley Caldera, where SNARL is located.

The UC reserve is ideally situated for the research carried out by the USGS team monitoring this part of the bi-state sage-grouse population and the vitality of the sagebrush ecosystem in this region. “We’re across the street from the majority of the mating sites,” McMillan says. “We even have grouse behind us on this hill.”

Grouse have a remarkable mating ritual called lekking. Males gather en masse at natural clearings, called leks, and dance for the females. Each lek usually has a dominant male, the king of the dance floor, as it were. Greater sage-grouse perform by bouncing two yellow air sacs on their chests, which produces a wobbling sound that “The Sibley Guide to Birds” describes as “weird.”

Grouse typically return to the same lek sites year after year. This is a boon for research and conservation efforts, providing a clear focus for yearly counts. Scientists have monitored sage-grouse in Long Valley for more than 70 years. “Given the bird’s fidelity to lek sites and long history of inhabiting the bi-state area, it’s not unreasonable to assume they’ve utilized these same leks for hundreds if not thousands of years,” says Tracy Misiewicz, the bi-state sage-grouse communication and data coordinator for the Eastern Sierra Interpretive Association. In 2024, the largest lek in the Long Valley had 118 male grouse at its peak.

The work conducted out of SNARL is part of a multi-agency effort to monitor the bi-state sage-grouse, with input from federal and state agencies, public utilities and independent volunteers. Researchers at USGS catch and tag female grouse with radio collars so they can track the animals. This enables them to find the birds’ nests, which they monitor for the rest of the season, checking in roughly every three days. Chicks will often remain in family groups from the time they hatch in mid-spring through fall. Monitoring the birds’ reproductive success enables scientists to follow population trends, and the health of the sage-grouse population provides a good indication of the overall health of the sagebrush ecosystem.