Books can do many things. They can transport you to faraway lands, confront you with intriguing ideas, and elicit empathy for people very much unlike yourself.

But there are many things books cannot do. They cannot physically harm you (unless you drop a heavy volume on your toe). They cannot change the past. And they definitely can’t alter your sexual orientation.

We are currently experiencing a concerted effort to keep certain books out of the hands of certain people. Like the plot of a literary novel, the campaign, driven by ideologues of wildly different persuasions, is complicated and sometimes contradictory.

It’s essentially symbolic but very real. It’s driven by both deeply held beliefs and political expediency. It’s reminiscent of previous controversies but different in terms of scale and scope.

And in the mind of one UC Santa Barbara scholar, it’s based on a fundamental misunderstanding about the nature of reading.

“It seems to me that those who want to challenge books attribute more power to books than they really have and don’t understand the ways reading actually affects us,” says Tim Dewar, associate teaching professor at the Gevirtz Graduate School of Education. “Reading doesn’t have magic power to transform you — and yet it does!”

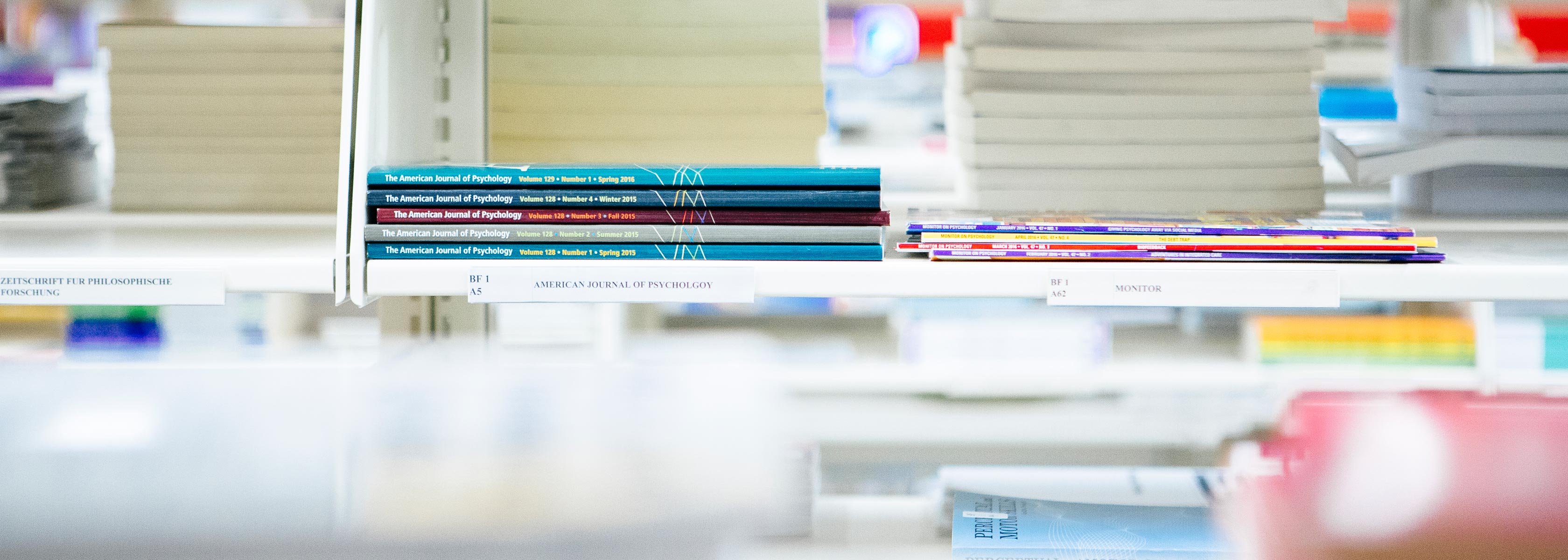

That power clearly scares a lot of people, especially as it applies to those seen as impressionable youngsters. In a recent report, the advocacy group PEN America found the scope of book censorship in the U.S. “expanded rapidly” over the nine months ending March 31, 2022. It listed 1,586 instances of individual books being banned, “including removal of books from school libraries, prohibitions in classrooms, or both.”

Moreover, it found 41% of these “are tied to directives from state officials or elected lawmakers,” a trend the organization calls “unprecedented.” These statewide initiatives are overwhelmingly in Republican-led states and reflect pressure by conservative activist groups.

Attempts to ban books from the left are less organized and have been primarily waged through social pressure as opposed to legislation. But the number of troubling anecdotes keeps growing. As a student in Burbank, California, recently wrote in The New York Times, her school district withdrew such classics as “Huckleberry Finn” from core classroom reading lists for fear they would offend contemporary sensibilities.

“What’s new to me is the inclination to restrict access to books coming from both the political right and the political left,” says UC Santa Barbara University Librarian Kristin Antelman. “It has traditionally come from the forces of cultural conservatism.”

Not anymore — or, at least, not exclusively. “I went to a bookstore in Amherst, Massachusetts, last summer, and I was shocked to find conservatives’ books criticizing the social-justice movement that were selling well elsewhere had been removed,” recalls William Warner, professor emeritus of English and comparative literature, who has taught and researched censorship for decades. “They were very proud of this when I asked them about this.”

The books under attack from the right tend to take the opposite point of view; many offer a more nuanced view of both American history and human sexuality than traditional textbooks. This has raised fears among socially conservative parents — much of it stoked by right-wing media — that their kids are getting indoctrinated with leftist values. Republican state legislatures have responded with bills that more clearly establish parental rights — bills that often involve making sure such books are in the “adult” or restricted sections of libraries.

It seems to me that those who want to challenge books attribute more power to books than they really have and don’t understand the ways reading actually affects us... Reading doesn’t have magic power to transform you — and yet it does!

“Parents do have an interest in their kids’ education, and there should be opportunities for them to provide feedback,” Antelman says. “The idea that any child of any age should have access to anything they want without their parents knowing is an extremist position, and probably a losing one.

“That said, writing into law what books libraries can have is a direct attack on intellectual freedom, free-speech norms and the First Amendment.”

“While there’s a long history of attempts to ban books, this recent effort feels more nationally driven than locally driven,” agrees Dewar. “Where there are individual parents who are concerned about what their children do or don’t read — rightfully so — this appears to be a concerted effort to push ideas, tactics and resources to individuals at the local level. I think mostly well-intentioned folks are being drawn into something that political partisans benefit from.

“My undergrads and I have looked at the most frequently banned and challenged books in high schools. Historically, they haven’t changed much from year to year — until the past two or three years. You find these brand-new titles. They’re not widely taught as instructional materials intended for a whole class. For a book (in that category) to race to the top of the most challenged books means somebody is sharing the titles.”

Alice O’Connor, professor of history and director of the Blum Center on Poverty, Inequality and Democracy, sees this as part of a larger effort to inhibit “the exercise of either political voice or pedagogical voice that doesn’t comport with a very narrow view of what American history and culture are all about.” She argues the threat from the right is far stronger than that from the left.

“Some of these right-wing campaigns are truly radical in their willingness to exert state power in unprecedented ways to subvert free expression and evidence-based scholarship,” she says. “It is embedded in a larger movement to undermine democracy. That’s deeply worrisome. There’s an utter disregard for the Constitution, for actual history and for people’s livelihoods.”

While Warner hopes and believes many of the new red-state laws will ultimately be declared unconstitutional, he also sees threats to free speech emerging from the left. He points to the argument from certain scholars that “racial and ethnic slurs are words that wound. They assault people. They cause harm, especially to disadvantaged groups. The distinction between saying ‘I hate you’ and hitting you is erased. Words are treated as acts. The distinction between citing something and using a word as a means of attack is also lost.”

Antelman, who has had leadership positions in several university libraries, says no one has come up to her and said, “This book contains outdated and offensive stereotypes and shouldn’t be on your shelves.” “But I’m afraid we’re headed in that direction,” she says.

“Over the last couple of years, libraries have been putting ‘content warnings’ on their metadata — the catalog that describes works in the collection. They say, ‘We recognize this book, or collection in the archive, contains language that is outdated and might be harmful.’ That’s a new concept. If you are saying the content is ‘harmful,’ why would you have it in the library? Why wouldn’t you remove it?”

Could such labels be a slippery slope to censorship? “I don’t want to be alarmist about this, but yes,” Antelman says.

If feelings of safety — inherently subjective criteria — trump freedom of expression, the implications are disturbing, especially since the argument can cut both ways. A teacher who was recently fired from a Florida school after putting up rainbow stickers was told such symbols were banned to “ensure that all students feel safe regardless of background or identity.”

The bizarre idea that straight students could somehow be harmed by rainbow flags clearly stems from the belief on the right that gay teachers or mentors are somehow “grooming” straight kids. This idea seems to be behind many of the attempts on the right to keep certain volumes out of both school libraries and school classrooms. Of the American Library Association’s list of 10 Most Challenged Books for 2020, five of them contain LGBTQ content.

This is a new variation on a historical pattern. “The most commonly challenged type of book in school libraries is probably the ‘exploring my body’ book, about sexuality and/or sexual orientation,” says Antelman. Warner notes that James Joyce’s “Ulysses” was initially banned from sale in the U.S. when a judge declared it obscene.

But a lot has changed since the 1920s. Given the proliferation of information on the internet and beyond, denying access to books is extremely difficult. The New York and Brooklyn Public Libraries recently set up websites where people anywhere in the country can get electronic copies of certain banned volumes.

So why are so many people effectively trying to hold back the tide?

“It is a scary time to be a parent,” says Dewar. “For a parent or community member who feels the world is spinning out of control, this feels like something you can get your arms around. ‘I can’t control the internet or what those darn kids are watching on their phones, but I can control what they have in the library.’”

“I see it as a symbolic action,” agrees Antelman. “I don’t think it’s dangerous in terms of people not having access to this information. We have a pretty open society. It’s a problem more on the symbolic level — the impulse to control the freedom to read, the freedom to be exposed to new ideas through books.”

How can advocates of free speech counter these efforts? “You have to fight for it,” stresses Warner. “You need school boards that are committed to plurality and letting a variety of positions coexist. There are institutional checks like tenure and academic freedom that need to be supported. It would also help to value diversity not just of race but of viewpoint.”

“Get beyond the defensive,” says O’Connor. “Tell a different story about the benefits, and the joy, of teaching in a free and open environment.”

Dewar’s answer is the simplest: “Read more! The more people read, the more they’ll understand how reading works, and the better they’ll be able to counter simplistic notions of the power of books.

“When we are carried away into another world — say, the world of Harry Potter’s magic — it can have real effects on us, but they’re not simplistic effects,” he says. “If it was the case that reading a book with a homosexual character can make you a homosexual, then reading a religious text would make you a saint!”