Photos by Matt Perko

Perched upon the Pacific Coast in sunny Goleta, UC Santa Barbara’s enviable seaside location was originally home to thousands of Chumash Indians, later serving as agricultural land and a World War II Marine air base. The military presence left an especially pronounced impact on Campus Point — the headland adjacent to the campus beach — which still bears asphalt and concrete foundations as well as carpets of invasive ice plant from that time.

Not for long.

With new funding from the state, UCSB’s Cheadle Center for Biodiversity and Ecological Restoration aims to remove the asphalt pad and replace invasive plants with native flora. The project will be done in collaboration with the Barbareño Band of Chumash Indians, to ensure the integrity of the site’s cultural resources and to create signage highlighting the location’s ecological, geological and cultural heritage. Work is set to begin this summer.

“Campus Point has so much potential,” said project lead Lisa Stratton, the Cheadle Center’s director of ecosystem management. “It’s this iconic headland that sort of defines UCSB, but it still bears the imprint of degradation from the military era.”

Restoration on the 7-acre bluff first began in 2012 with the construction of a boardwalk stairway, using money from the university, the Coastal Fund and the California Coastal Conservancy. The new award, from the California Natural Resources Agency, will cover four years of work to ensure the area is stabilized and fully restored.

Plans include reestablishing the mixture of habitat types that the site once featured, including beach dune, coastal scrub and woodland. Ice plant, which smothers native plants and provides little habitat or food to the region’s wildlife, has overgrown the bluff since it was introduced in the 1950s. Tarps are being used to starve them of sunlight and convert them into fertile mulch for local shrubs.

Chris Berry examines an area of ice plant which is slated for removal during the restoration.

The project team also will remove some fallen trees and add native fruiting trees like toyon, elderberry and lemonade berry to support the small woodland on the lagoon side of the headland. Acorns planted in 2005 have already begun to restore the canopy in that area.

The team also aims to determine the unique and historical character of Campus Point’s ecology. “Coastal sage scrub is a broad plant community, but I’d say there’s a specific flavor to it in the varying regions of California, such as coastal Goleta,” said Chris Berry, the Cheadle Center’s Campus Lagoon steward.

The center already has had great success in reintroducing increasingly rare native wildflowers and annuals, which are important for supporting native bees, butterflies and other components of the food web. “Unfortunately, these annual flowering forbs tend to get lost and ignored,” Stratton said. “They’re really vulnerable to invasive annual grasses, so bringing them back requires long-term management, controlled burns and careful weed control.”

Controlled burns on Lagoon Island have also been effective. A survey of the burn plot in 2020 found 84% native plant cover composed of 33 different species. In contrast, invasive plants accounted for barely 1% of the burned area, according to Berry. While there is no plan to carry out controlled burns at Campus Point, the Cheadle Center will expand burns on Lagoon Island.

Local community members, including school groups, student workers and interns, will contribute to the restoration project — as will members of the Barbareño Chumash.

“Part of our role is to diligently watch the work as it happens, and to keep an eye out for any significant resources and make sure that they are handled with the utmost dignity and respect,” said Eleanor Fishburn, chairwoman of the Barbareño Band of Chumash Indians. The whole area around Goleta Slough is environmentally and culturally sensitive, with a long history of Chumash presence.

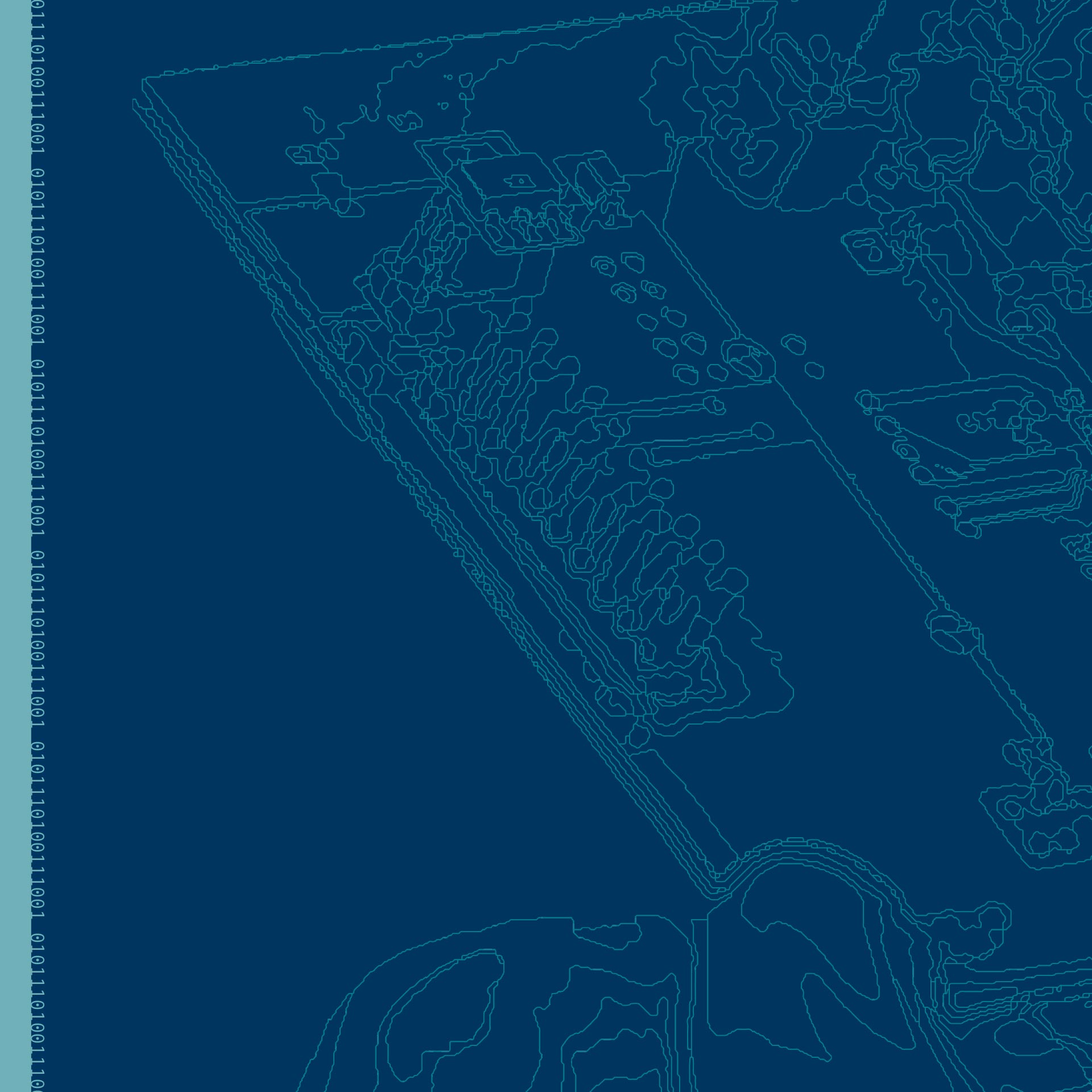

Campus Point was undoubtedly a familiar location to past Chumash people. Historic notes and maps preserve the site’s Chumash name, Sismikiw. The nearby Goleta Slough (Sitiptip in Chumash) was once a sizable shallow bay that hosted many villages. It was among the most densely populated areas in all of pre-contact California — a veritable metropolis.

Natural processes and human activity dramatically reshaped the area around campus over the past 200 years, altering the ecology and cultural record. Large debris flows in November 1861 turned the bay into more of a shallow lagoon. Then in WWII, government airfield construction filled in most of the Goleta Slough, leaving the saltmarsh we see today. This process destroyed half of Mescaltitlan Island (or Helo’), the historical site of a major Chumash village.

Slated for installation as part of the restoration, interpretive signs will inform future visitors about the site’s flora and fauna, geological processes and cultural heritage. The goal is to foster a connection with the ecology, culture and history of the location.

“The site is really accessible to the campus community,” Stratton said, “and the project will restore this amazing headland for generations to appreciate and enjoy.”