Grief and joy are inseparable, Kahlil Gibran says in his 1923 classic “The Prophet”: “Together they come, and when one sits alone with you at your board, remember that the other is asleep upon your bed.” For France Winddance Twine, waking up joy after her mother died by suicide required a blowtorch.

In 2008, six years after her mother May died, Twine, a UC Santa Barbara sociology professor, was carrying out ambitious research, including her seminal texts on feminist race theory, a concept she introduced. But she wasn’t dealing with her emotions around May’s death, and in addition to the grief, she was experiencing impostor’s syndrome at work.

“I was on sabbatical in New York when my mother committed suicide,” Twine says, “and I didn’t go to therapy because in my family, you handled things on your own. I came back and I did my work. Years went by in which I was a workaholic. I was overproducing. When I was hired, there were no Black women in the Department of Sociology and only a few Black people in the social sciences. My solution was to work.”

Twine had always been close to her mother, and now she was feeling alone and exhausted. Finally, she was ready to process her mother’s death; she drove up the coast from Santa Barbara to Big Sur’s Esalen Institute, where she planned to participate in a grief retreat.

Once in the group, she saw a familiar face and knew she needed to find another group; at the time, she wasn’t ready to share her grief with people she knew from work. So she asked to be put into the only other retreat taking place: encaustic art.

Dating back to the first century, painting with hot wax, known as encaustic art, was common in ancient Greece and Rome. The oldest surviving encaustic panels are portraits of mummies in Egypt from 100 to 300 A.D.

“I had no idea what I was getting into, but I went into it to process my grief,” she says. Soon, she was making fire and painting with a blowtorch and hot wax. Wielding an open torch, she burned artworks in 12-by-12-inch pieces of furniture-grade birch wood. She was terrified that she’d blow something up.

“I chose to do a triptych and the first piece was of my mother’s spirit before she had us,” she says. “It was all about processing my feelings.” To her shock, the piece was awarded first place at the end-of-retreat exhibition and Twine had renewed her practice of making art — a side of her that she put away when she was in graduate school. Growing up, she made her own clothes and was interested in textile art. She was inspired to take a weaving class by her paternal grandmother, who was Native American. “I had a loom and I used to weave things; I liked the tactile nature of it,” she says. “But at grad school at UC Berkeley, I couldn’t afford it. So, I feel like I gave up weaving for my Ph.D.”

She later attended a workshop in San Francisco and then another the following year. Making art had become a way to get in touch with her spiritual side. She says it helped her get back in touch with joy, a hope she had regained after reading in “The Prophet” that “the sorrow you experience carves more room for joy.”

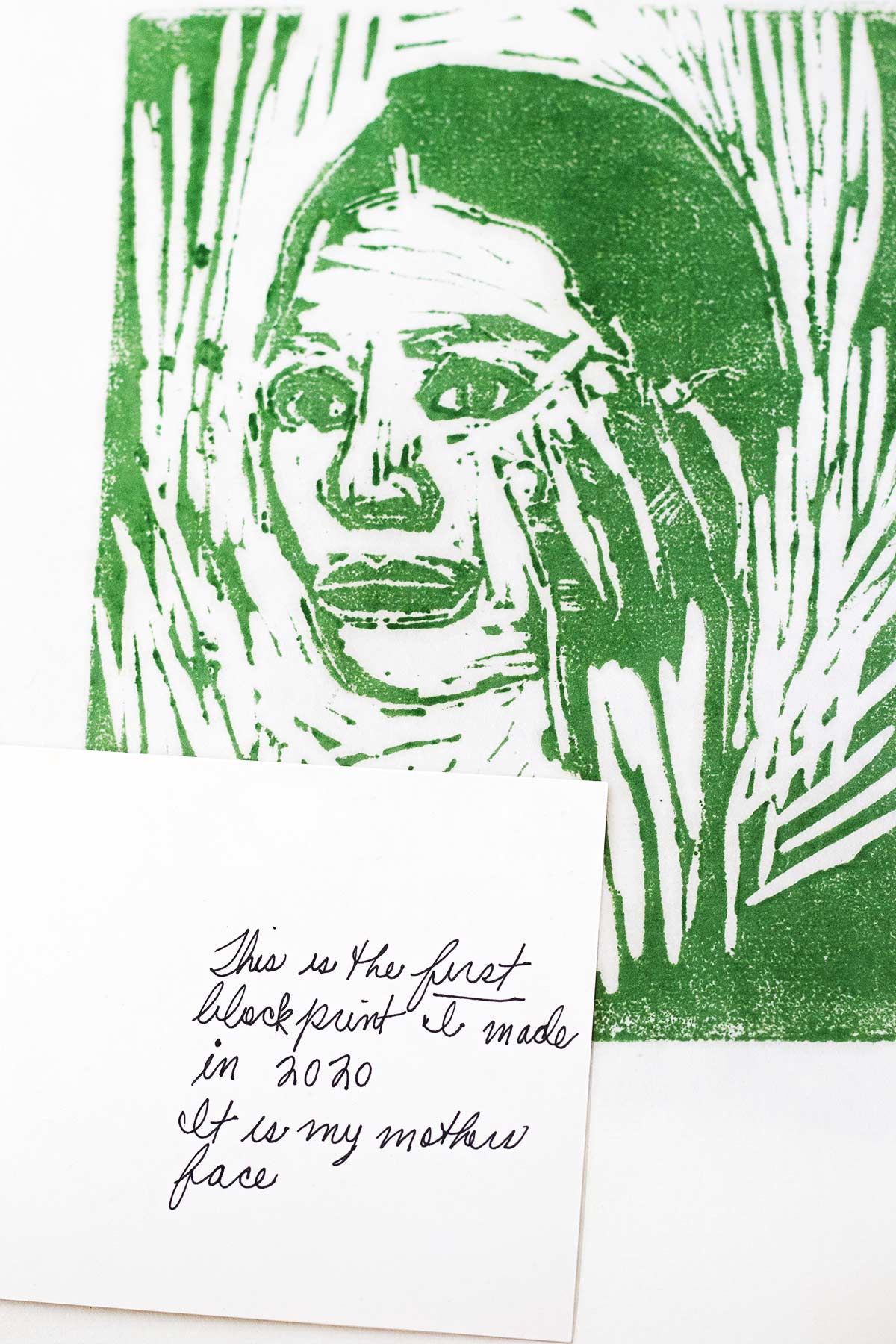

This was needed as Twine endured the deaths of three family members in 2020 during the pandemic. Teaching two classes online at the time, she knew she needed to deal with her grief. She had recently received temporary custody of her young nephew Selasi and thought that doing art with him would be a way to connect, and to help shift her mindset. But instead of a blowtorch, which is not baby proof, with Selasi she took up block printing, which can be done with supplies as simple as raw potatoes.

On her own, including through an online class with artists from Chicago, where she is from, Twine began woodblock printing. Her first block print was of a face. “It scared me because it came out so powerful; it was my mother’s face,” she says. “I was frightened by the emotions that came out of my first prints.”