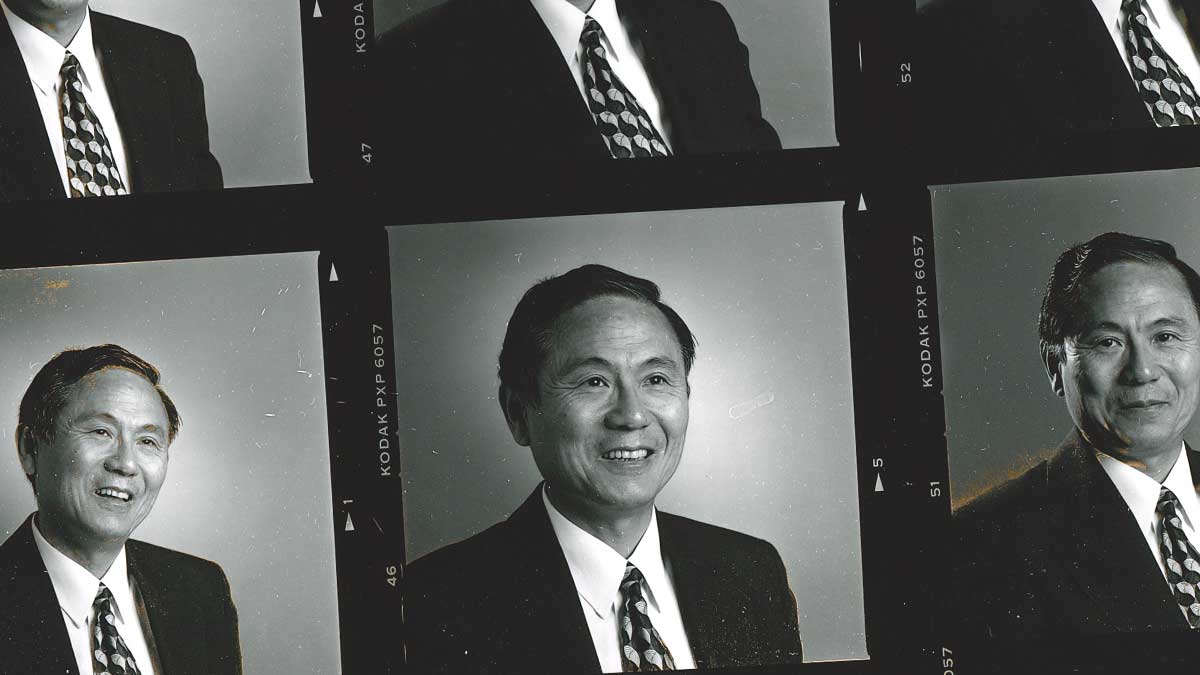

Photo by Jeff Liang

From wonder to invention

From wonder to invention

Angela Belcher turns lifelong curiosity into cancer research and new tools for early detection

by Keith Hamm

As far back as she can remember, Angela Belcher BS ’91, Ph.D. ’97 wanted to be an inventor. She was not born into a family of scientists or engineers or researchers. She did, however, grow up near Rice University, in Texas, where fond memories resonate from long afternoons in the library, surrounded by what her young mind estimated to be all the world’s knowledge.

Book by book, she fueled an innate drive for learning and novelty.

“I followed that passion,” Belcher says, “and now I can call myself a chemist, an engineer, a biological engineer. But to me, I’m an inventor.”

The lifelong body of work Belcher is best known for focuses on nanoparticles. Her studies in that field began at UC Santa Barbara, where she earned a College of Creative Studies undergraduate degree in biology and followed up with a Ph.D. in chemistry. In 2024, she won the National Medal of Science. She’s also a MacArthur Fellow and a member of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, the National Academy of Inventors and the American Academy of Arts & Sciences.

Starting at UCSB, Belcher’s early research explored controlling nanostructured materials — a nano, in this case, is a billionth of a meter — at the genetic level. She was inspired by the structure of abalone shells, which are 3,000 times stronger than their geologic counterparts. From there, she pioneered how genetically modified viruses can self-assemble into very strong nanoscaffolds that can be coated with inorganic materials to create, for example, advanced batteries, solar cells and semiconductors.

These breakthroughs combined scholarship from biology, materials science and engineering. Such interdisciplinary research and problem solving have been hallmarks of the College of Creative Studies since its inception in 1967.

“Creative Studies shaped everything about my life,” Belcher reflects. “What I wanted to do was pick and choose topics and put them together in nontraditional ways. I think problems get solved at these interfaces of scientific disciplines.”

In 2002, Belcher joined the faculty at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where she has made further advancements in materials science and, in 2009, she joined MIT’s Koch Institute, which brought together engineers, scientists and clinicians from diverse backgrounds to come up with new ways to diagnose and treat cancer.

One of her first projects was to help develop a method for using shortwave infrared light to image cancer cells, a technology now used by doctors during cancer surgeries.

Her new focus on cancer research hit home for Belcher. Her mom had struggled with uterine cancer for much of her life and died early from breast cancer, the same disease that had killed Belcher’s maternal grandmother in her 40s. Belcher has also lost two MIT colleagues to ovarian cancer, she says.

“Both were women in the National Academy of Sciences, top of their field. Both were in Boston, which is among the very best medical communities in the world. And both had great health insurance — but we couldn’t save their lives.”

A lot of her work now focuses on ovarian cancer, which is very difficult to detect in its early stages. To illustrate her frustration with that diagnostic fact, Belcher points out that, in 2020, NASA was able to land a probe on asteroid Bennu as it tumbled through space at 63,000 mph, 200 million miles from Earth. At the same time, clinicians weren’t able to look a few inches into a stationary woman’s abdomen to find a 2-millimeter tumor.

Drawing from her field of expertise, Belcher and her team are developing new nanomaterial and optical systems to detect tumors early on.

“A lot of what I do is to try to address these limitations on why we can’t find ovarian cancer at early stages, when you can remove it before it metastasizes,” she says.

“We are working to bring passionate and creative people together with ideas to solve around these bottlenecks,” she says. “At UCSB, I learned how to push the boundaries. I learned how to be brave enough to say that this is unacceptable. I learned to not accept that something is impossible.”