Where the human mind, and human nature, meet the natural world

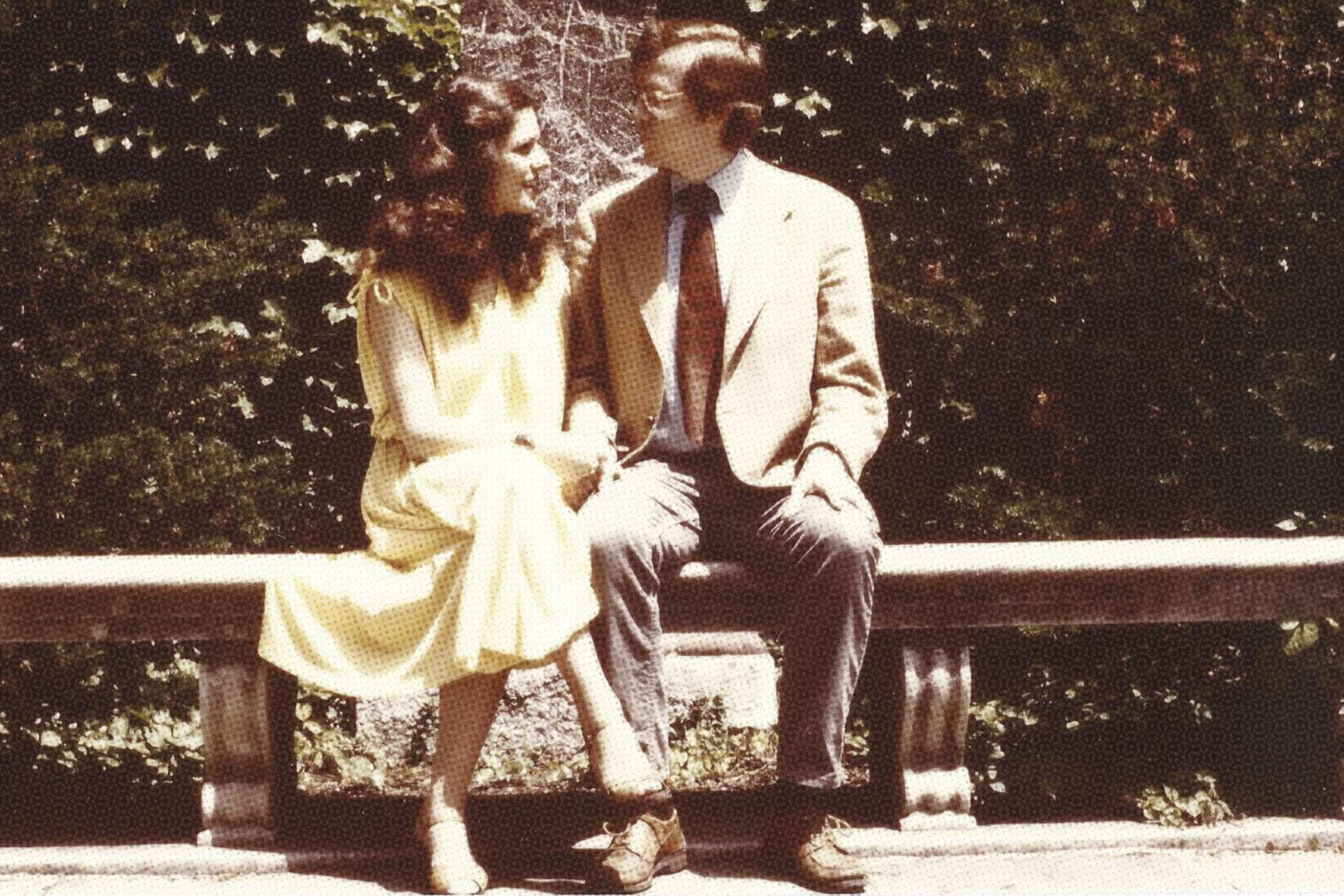

Leda and John, in the beginning. June 1979

PHOTO: COURTESY

Where the human mind, and human nature, meet the natural world

By Andrea Weir

SITTING IN A SUPERCUTS one day perusing a copy of Esquire magazine, psychology professor Leda Cosmides was struck by a pre-millennium headline — “The Red-Hot Centers of Genius: Welcome to the Next American Century.” Out of curiosity, she scanned the listing. There, two places below CalTech Pasadena and with Disney Imagineers on one side and the National Center for Atmospheric Research on the other, was UC Santa Barbara’s Center for Evolutionary Psychology (CEP).

“Leda Cosmides, John Tooby, and a powerful coterie of evo-psychs,” the author wrote, “are kicking the neurons out of classical and cognitive psychology in favor of more Darwinian explanations for why people behave — and misbehave — as they do.”

That was almost 25 years ago, and it still pretty much sums up the whole of the Center for Evolutionary Psychology. Since it was co-founded — and subsequently co-directed — by Cosmides and Tooby in 1994, the center, celebrating its 30th anniversary, has pushed the boundaries of what’s understood about universal human nature and behavior.

Tooby, a professor of anthropology, died in November, but the center continues with Cosmides and Dan Conroy-Beam, associate professor of psychology, at the helm. And, of course, Tooby’s legacy will remain ever-present.

“Crediting John with inventing the academic field of evolutionary psychology doesn’t quite do him justice,” said Harvard University professor Steven Pinker, a friend, colleague and frequent CEP visiting scholar. “It wasn’t just inventing a field in academia, but it was really connecting the human mind and human nature to the natural world in a deeper and more systematic way than anyone had ever done before.”

While Tooby and Cosmides weren’t the only people who contributed to the field, Pinker noted, Tooby “more than anyone made it intellectually coherent.”

“He and Leda in a set of papers written in the period since they were post-docs laid out questions the field had to answer,” Pinker continued. “Questions like, ‘Since natural selection runs on variation, doesn’t that mean we can’t say anything about human nature since we’re all different?’ Or, ‘Is natural selection just a bunch of afterthe-fact just-so stories? Can you tell an evolutionary story about anything?’ All these misconceptions, I think John and Leda addressed explicitly and debunked a lot of misunderstandings.”

From the beginning, the CEP has taken a multidisciplinary approach that brings together evolutionary biology, cognitive science, human evolution, hunter-gatherer studies, neuroscience and psychology into a new approach to discovering the mechanisms of the human mind and brain.

“This is where we trained everybody, including ourselves,” Cosmides said of the center, where she and Tooby would jointly advise anthropology and psychology graduate students. But they weren’t limited to those fields. “We’ve had students come through who were studying evolutionary psychology in film and literature, political science — anyone from a discipline where a model of human behavior might be relevant.”

Cosmides and Tooby came to UC Santa Barbara in 1990, and two years later published their seminal work, “The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and the Generation of Culture” (Oxford University Press). This edited volume introduced evolutionary psychology as a field of study.

They modeled the Center for Evolutionary Psychology — more specifically, their CEP seminars — after the Simian Seminars they attended while undergraduate and graduate students at Harvard University. “Irv DeVore was a biological anthropologist, and the Simian Seminars would happen at his house,” recalled Cosmides. “Everyone who was interested in evolution and behavior would come; it didn’t matter what field they were in. And all these amazing people would come and speak — Richard Dawkins, John Maynard Smith, Dian Fossey. That’s what we wanted to recreate here.”