A graduate student researcher in the Pennathur lab holds a beaker.

Photo by Matt Perko

Research Highlights Spring/Summer 2023

Research

Beware of resting phone face

When it comes to raising children in the digital age, one of the worst things a parent can do is give their kid a smartphone and hope for the best. Turns out, same goes for the grownups. Research suggests that the emotional intelligence of kids can be adversely impacted by their parents’ smartphone use — that all-too-common scene of a caregiver engaging with a screen with their child nearby seeking attention — because it appears to children as a lack of responsiveness. In addition, parental phone use is associated with “still face,” an expressionless appearance that’s often interpreted as depression, which can further impact a child’s development of emotional skills. “The takeaway is for parents to be more mindful of how often they are using their phones around their children,” says communication professor Robin Nabi. “Where their eyes are sends a message to their children about what’s important.”

Photo: Istock

Photo: Jim Evans, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

What's that smell?

The delicate fragrance of jasmine is a delight to the senses. The sweet scent is popular in teas, perfumes and potpourri. But take a whiff of the concentrated essential oil, and the pleasant aroma becomes almost cloying. Indeed, part of the flower’s smell comes from the compound skatole, a prominent component of fecal odor. Our sense of smell is a complex process that involves hundreds of different odorant receptors working in concert. The more an odor stimulates a particular neuron, the more electrical signals that neuron sends to the brain. But researchers discovered that these neurons actually fall silent when an odor rises above a certain threshold. Remarkably, this was integral to how the brain recognized each smell. “It’s a feature; it’s not a bug,” says Matthieu Louis, an associate professor of molecular, cellular and developmental biology.

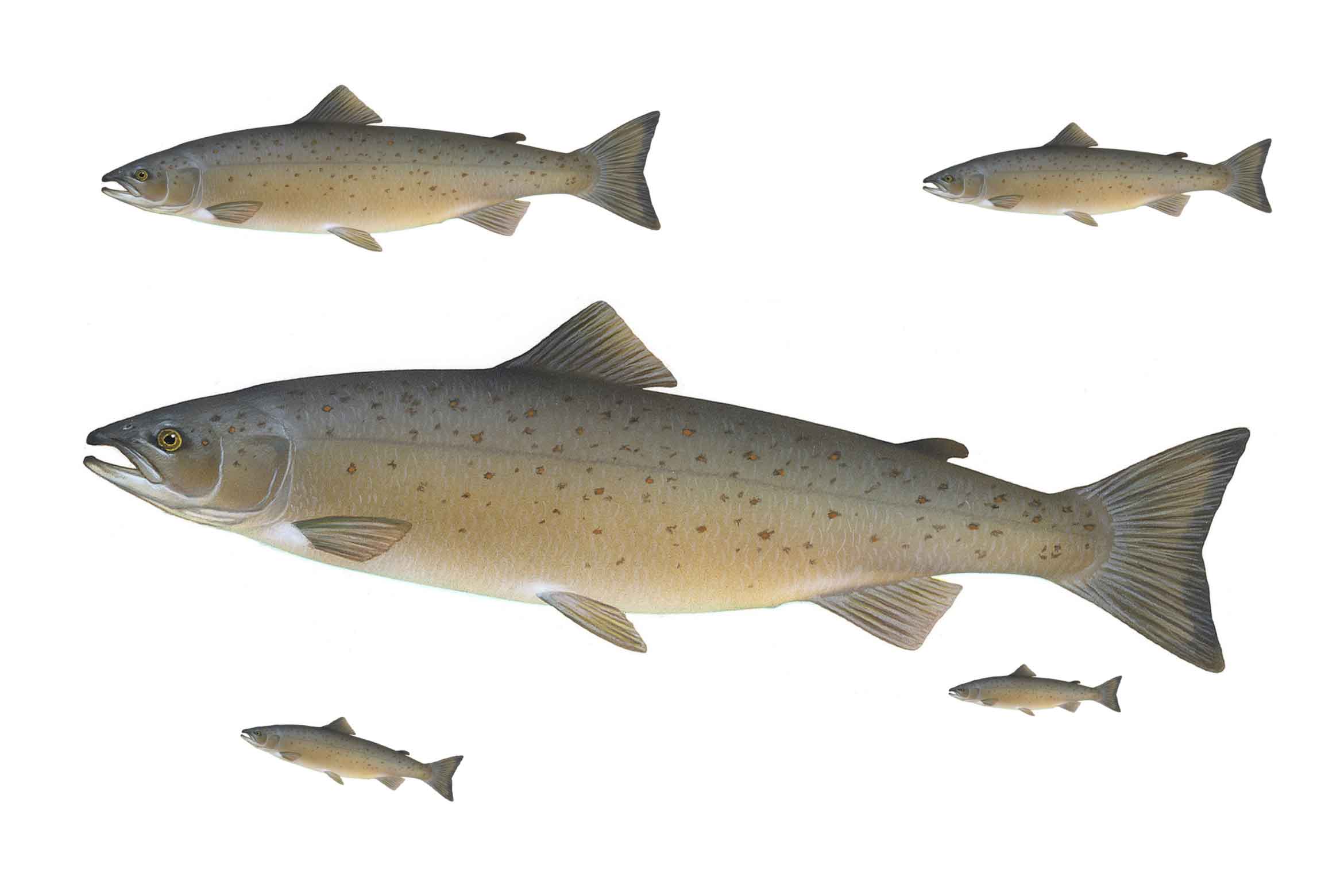

Chicken of the sea

We love our chicken. We love our salmon. Thanks to how we farm these two popular proteins, their environmental footprints are surprisingly similar. The key is in the feed, according to researchers. An international team examined how we raise these two highly popular animals for consumption, focusing in particular on dynamics between land and sea. They found that 95% of the cumulative environmental footprint of chicken and salmon (greenhouse gas emissions, nutrient pollution, freshwater use and spatial disturbance) is concentrated on less than 5% of the planet, with 85.5% spatial overlap between the two products, due mostly to shared feed ingredients. “Chicken are fed fish from the ocean, just as are salmon, and salmon are fed crop products like soy, just as are chicken,” says marine ecologist Ben Halpern, director of UC Santa Barbara’s National Center for Ecological Analysis & Synthesis. “In a sense, we really do have ‘chicken of the sea.’”

Timothy Knepp, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Courtesy of the artist

Recasting the Renaissance

Artist Harmonia Rosales employs the pictorial tropes of Renaissance painting to reimagine tales from the West African religion Yorùbá. A show of her work at the Art, Design & Architecture Museum, conceived and curated by classicist Helen Morales, inspired a national touring exhibition and a new catalog. Morales’ research considers myths as foundational beliefs and spaces for cultural resistance. Rosales’ paintings first caught her attention because of how they engaged with, and supplanted, Greek mythology. Rosales’ style of painting mirrored canonical Renaissance works that Morales knew well, such as the Sistine Chapel, with a distinct twist: By recasting the European Renaissance style to depict the West African slave trade and tales of the Yorùbá spirits, Rosales contributes to a rewriting of art history’s master narrative. “Rosales focuses on what unites us all,” says Morales, Argyropoulos Professor of Hellenic Studies. “It’s social justice, but with an optimistic trajectory. Rosales is more interested in what connects us than what divides us.”