Wax cylinders with audio recordings from the late 1800s of various Chinese dialects were recently acquired by the UCSB Library

PHOTO: MATT PERKO

Wax cylinders with audio recordings from the late 1800s of various Chinese dialects were recently acquired by the UCSB Library

PHOTO: MATT PERKO

by Johannes Steffens

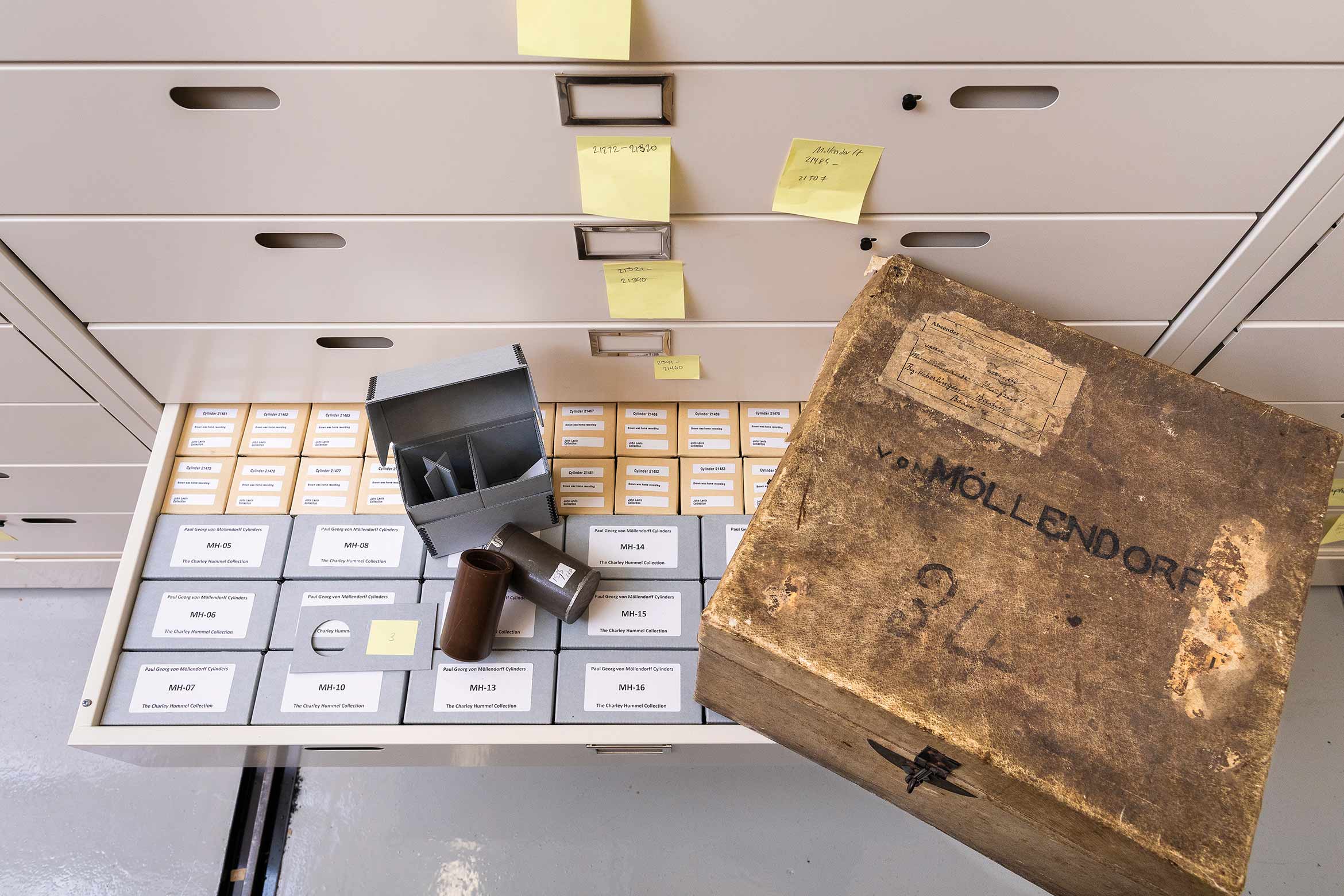

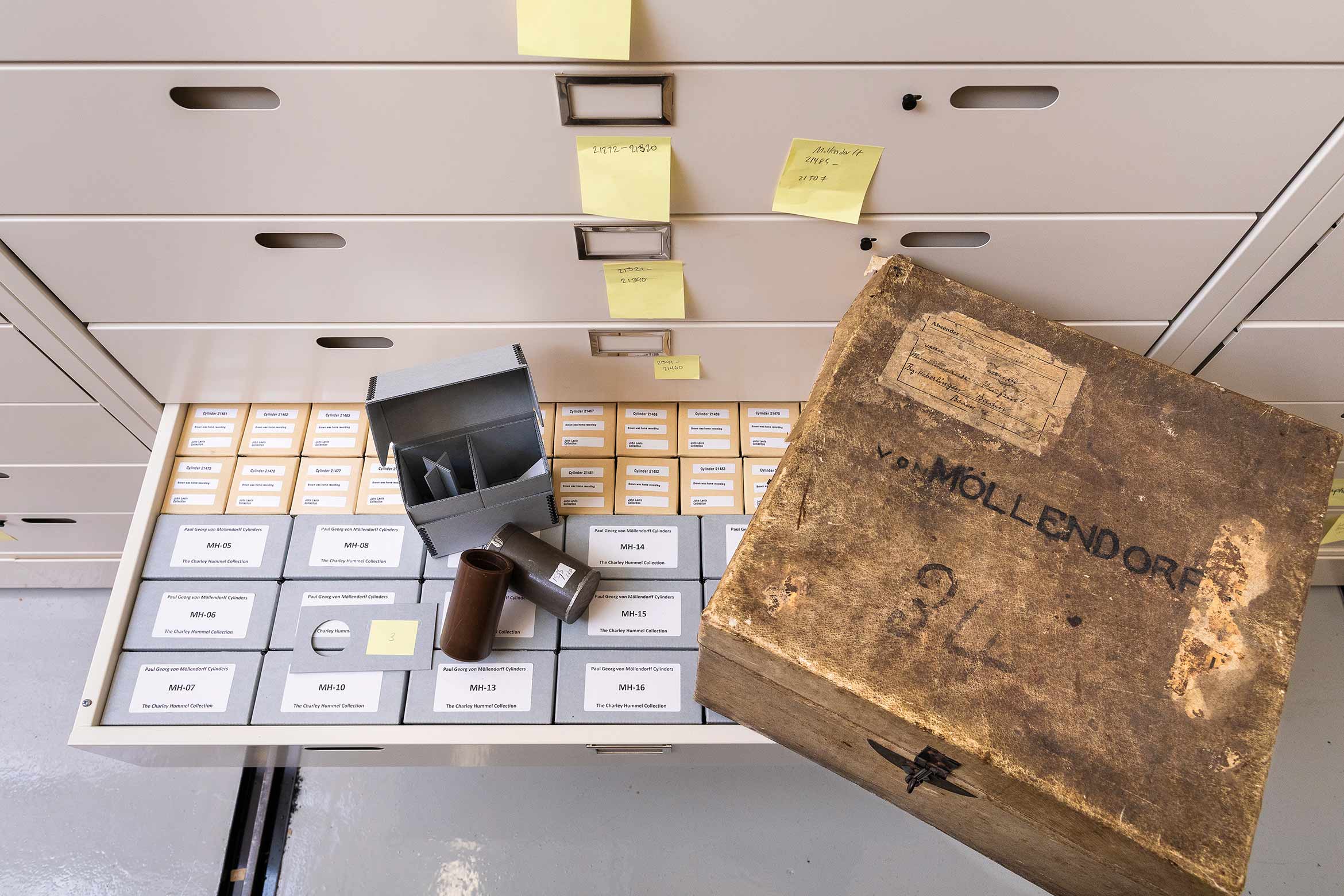

Widely considered the earliest form of audio recordings, wax cylinders offer rare glimpses into how the world sounded in the distant past. Indeed, a unique collection from China, recently acquired by the UC Santa Barbara Library, provides an elusive glance into the history of the Chinese language and dialects now considered critically endangered or extinct.

The Paul Georg von Möllendorff Chinese cylinders, a collection of 16 recordings from the late 1800s, feature Möllendorff (1847-1901), a German linguist who recorded recitations of a popular, celebrated poem, “Returning Home” by Tao Yuanming, in various Chinese dialects, reflecting the differences in regional languages at the time.

The acquisition was made through the library’s Early Recordings Initiative (ERI), a public-private partnership to ensure that cylinders like Möllendorff’s are preserved and made accessible to future scholars.

“The Möllendorff cylinders are essentially a sonic Rosetta Stone that holds the key to understanding past cultures,” says John Levin, a cylinder collector and ERI co-founder. “Just as the visual arts give us a glimpse into our collective history, audio recordings can offer insight into the history of a specific time and place that is invaluable to researchers.”

The cylinders could have easily been lost to obscurity if not for the curiosity of collector Charley Hummel and the sleuthing work of two distinguished musicologists. In the early 2000s, Hummel, a renowned American collector of phonograph machines and records, came across a mysterious hide-covered box of Chinese cylinders in a phonograph shop in Paris and was instantly intrigued. The cylinders appeared to have Chinese content on them and the box was labeled “MÖLLENDORFF.”

Hummel purchased the cylinders intending to research their history and asked historians Patrick Feaster and Xiaoshi Wei to help him unravel the mystery of their provenance. After Hummel’s death in 2023, the library’s interest was piqued by historical research from Feaster and Wei, who identified the recordings and studied their connection to Möllendorff.

In the 1890s, while serving as a diplomat and commissioner of customs at Ningbo, China, Möllendorff undertook an ambitious project to document and classify Chinese languages for the 1900 Universal Exposition in Paris. He asked speakers representing various Chinese languages to recite the same poem into a graphophone and then transcribed the results phonetically. He then sent the cylinders to Léon Azoulay, a prominent figure in the Société d’Anthropologie de Paris, to feature at the exposition as part of a “phonographic museum” where visitors could take an audio tour of cultures around the world. Azoulay later published a full catalog of the museum’s contents, including the Chinese cylinders, explicitly identified as Möllendorff’s.

Feaster and Wei theorized that “Möllendorff intended to send additional sets of cylinders to London, Berlin and St. Petersburg, to complement the set he had sent to Paris, but his unexpected death on April 20, 1901, derailed these plans.”

The location of the cylinders in the following 100 years until Hummel acquired them is unknown. As part of the library’s Performing Arts Collection, the cylinders’ long-term preservation and accessibility is ensured.

As part of ERI, they will likely receive more scholarly attention. The cylinders are unique to the collection because they were created as linguistic artifacts, rather than for entertainment purposes.

“The Möllendorff cylinders are undoubtedly more valuable as part of the public domain rather than a private collection, where they would have remained largely unpublished,” says David Seubert, performing arts curator. “At UCSB, they have the potential to influence scholarship and research with partners in France, where the remaining cylinders live, and with other international centers of musicology. This is exactly the kind of effort that is supported by ERI, which strives to prevent valuable early recordings from disappearing into obscurity.”